Editor's Note: Peter's latest "Fumes" column proved to be quite popular, and since we feel the Chaparral/GM relationship is an important historical milestone to take note of in American motorsports - and Paul Van Valkenburgh's book deserves to be recognized - we're going to run it again this week. Peter will be back with a new "Fumes" next week. -WG

By Peter M. DeLorenzo

Detroit. As many readers know, I've written about the future of racing and the ramifications of a changing world on the sport in this space often. Last week's column - "When All Racing Becomes 'Vintage' Racing" - was another in a long line of columns concerning the future of the sport. For people who love and are enthusiasts of the sport, and for people directly involved in the business of motorsport, the future should be of serious concern and my reasons for writing about this subject on a continuous basis are well documented.

It's easy for the players in this sport, the team owners, drivers, technicians, etc., to get lost in the immediacy of what they do. Supporting a modern racing organization with the proper funding to retain talented employees while chasing sponsorship is a never-ending task, and it understandably must be a top priority. But while doing this it's easy to lose sight of the Big Picture because, after all, once a team's personnel and budgets are secured, overriding concerns about the overall health of a racing series become secondary.

But when a given racing series plays out before empty grandstands and excuses are continuously made about minuscule TV ratings, and the key players involved operate as if wearing blinders while insisting that everything is all good, this is what I call "racing in a vacuum." And it's a seriously myopic way to go about the business of racing, because to pretend that this is all going to continue on without repercussions and consequences is to display a level of naivete that almost defies understanding. Witness the Brian France remarks at Homestead-Miami Speedway last weekend, whereupon he insisted - yet again - that everything is good with NASCAR, which is flat-out laughable as even the most prominent NASCAR teams are struggling to find sponsors. Or the fact that the sport of Indy car racing is almost back where it started, which means that there's the Indianapolis 500 and a bunch of other races of varying degrees of substance making up the IndyCar Series schedule. Not to mention the glacial pace of change in F1, which has become a recurring joke, while the players argue about new engine rules for 2022.

I constantly prod and push the powers that be in this sport to get their heads out of their asses and take the long view, because if they fail to do so, racing will continue to fade in importance except for a few premier events, which would be a real shame.

If you follow me on Twitter (@PeterMDeLorenzo) you know that I've been posting images and commentary covering a lot of the compelling historical stories of racing's golden years. Of late I've focused on the story of the fabulous Chaparrals of Jim Hall, which marked one of the high points of "blue-sky" thinking and advanced technical developments in the sport. Through the course of my Twitter postings, one of my Twitter followers was incredulous to find out that Chevrolet was deeply involved in a technical partnership with Jim Hall, one that was completely kept under the table due to the fact that some of the suits on the famous 14th Floor of the GM Building were decidedly anti-racing.

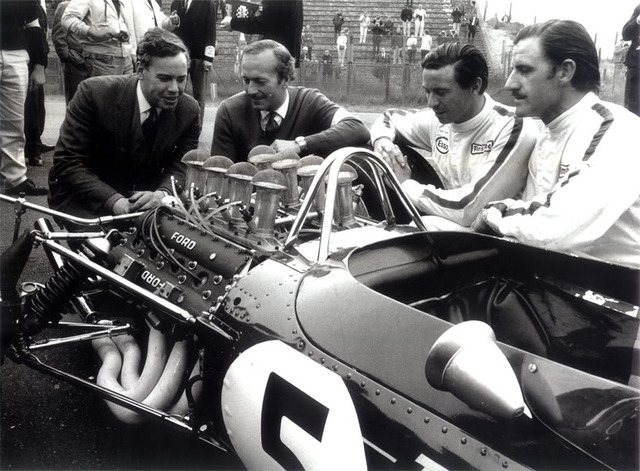

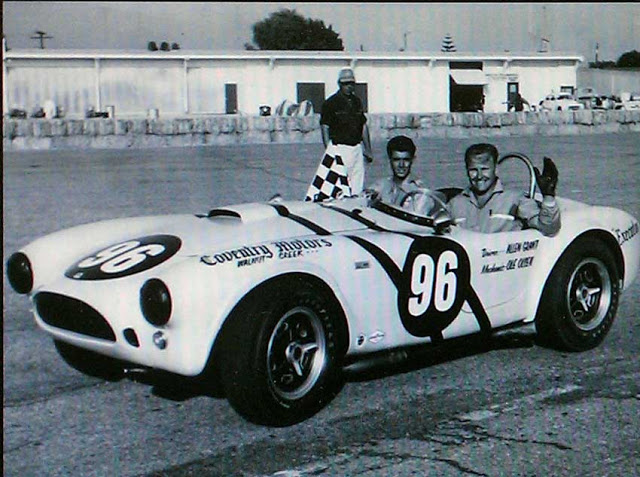

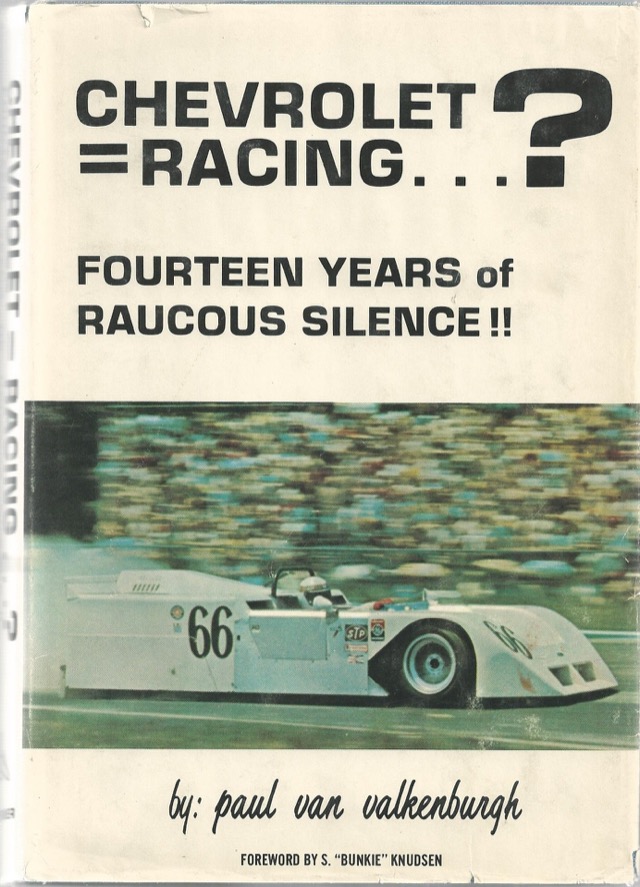

Though I prefer the way Ford went about its racing in the 60s, which was part of an aboveboard, orchestrated marketing push called "Total Performance," the story of the Chaparrals and other racing endeavors by GM/Chevrolet Engineering's True Believers and Best and Brightest is one of the most fascinating stories in the history of motorsport. If you can get your hands on Paul Van Valkenburgh's vivid account of those incredible years - "Chevrolet = Racing...? Fourteen Years of Raucous Silence!!" - you will be amazed at the stories and photos documenting Chevrolet Engineering's deep involvement in the Chaparral program, and other racing forays with John Mecom, Roger Penske and a host of others.

The reason I'm bringing this up is that those fourteen years coincided with one of the most creative eras in motorsports history, long before the sport devolved into a maize of restrictions and specifications. I would like to think we can somehow muster a new era of creativity in racing again, but as long as "racing in a vacuum" is racing's standard operating procedure, I'm afraid the sport will continue spinning its wheels along the road to its inevitable decline.

And that's the High-Octane Truth for this week. (Amazon)

(Amazon)

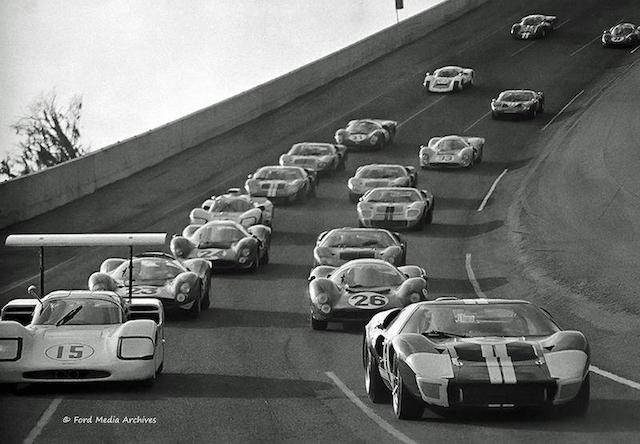

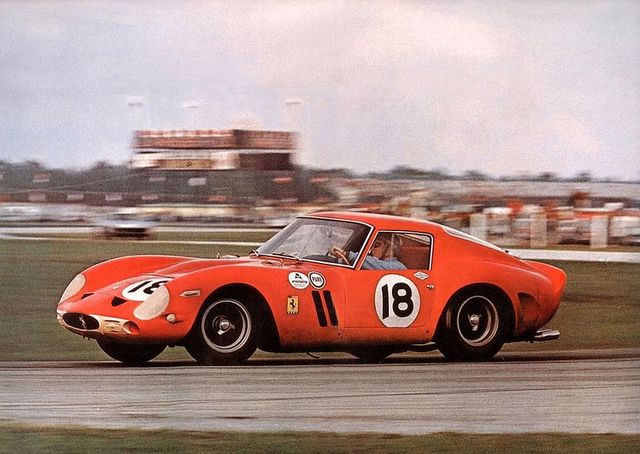

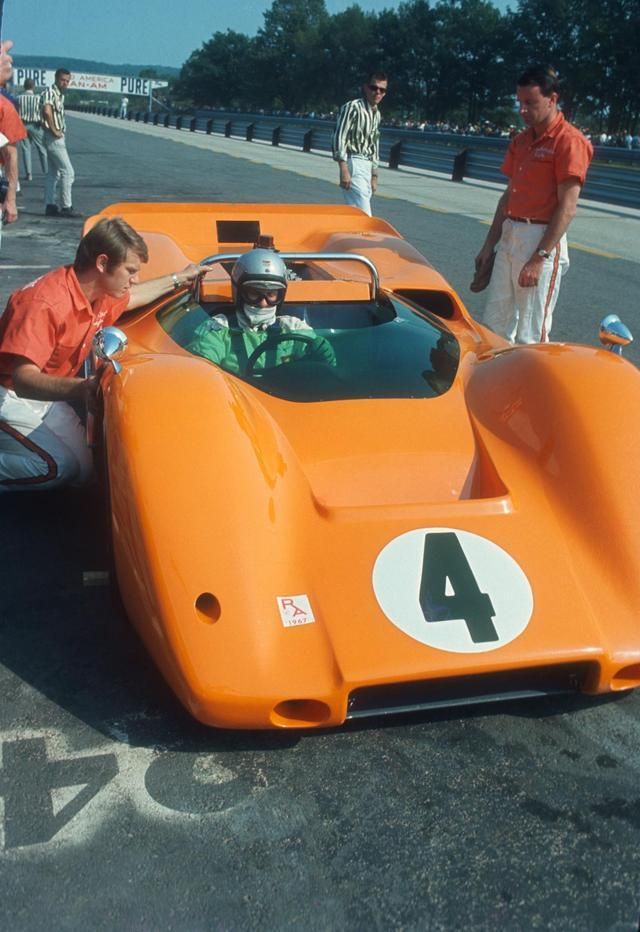

"Chevrolet = Racing...? Fourteen Years of Raucous Silence!!" was Paul Van Valkenburgh's vivid account of GM/Chevrolet Engineering's under the table racing programs. A fascinating read. Elkhart Lake, Wisconsin, 1965. Hap Sharp in the No. 65 Chaparral 2A (with 2C modifications) drives through the paddock @roadamerica. The Chaparral team swept the Road America 500, finishing 1-2.

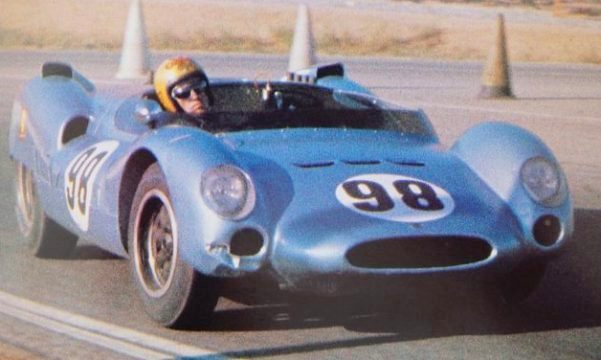

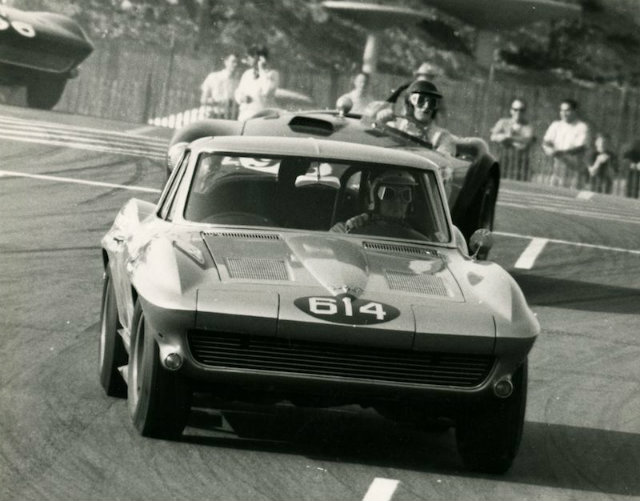

Elkhart Lake, Wisconsin, 1965. Hap Sharp in the No. 65 Chaparral 2A (with 2C modifications) drives through the paddock @roadamerica. The Chaparral team swept the Road America 500, finishing 1-2. The Corvette GSIIb was the Chevrolet Engineering research version of the Chaparral 2 and its iterations.

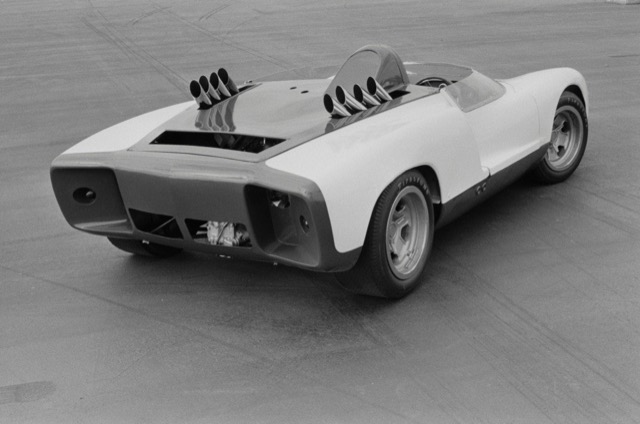

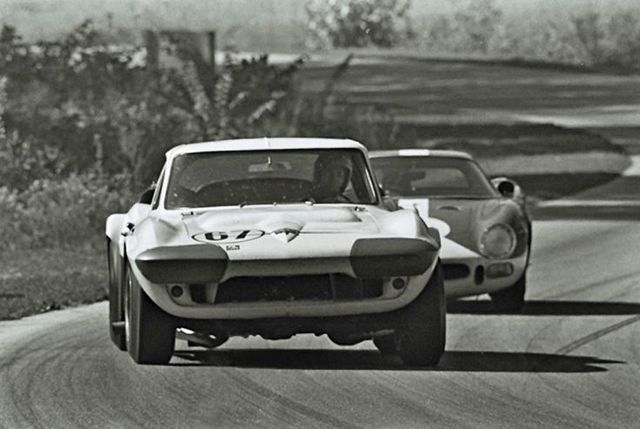

The Corvette GSIIb was the Chevrolet Engineering research version of the Chaparral 2 and its iterations.

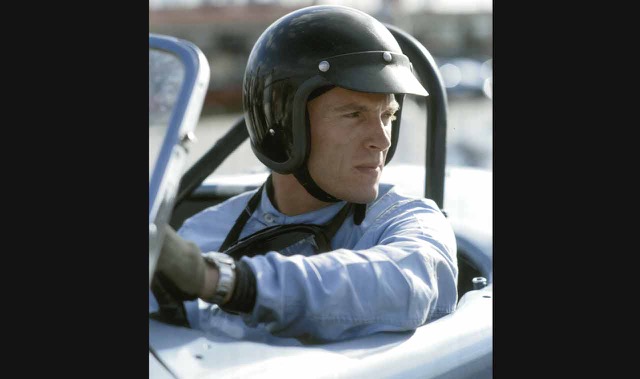

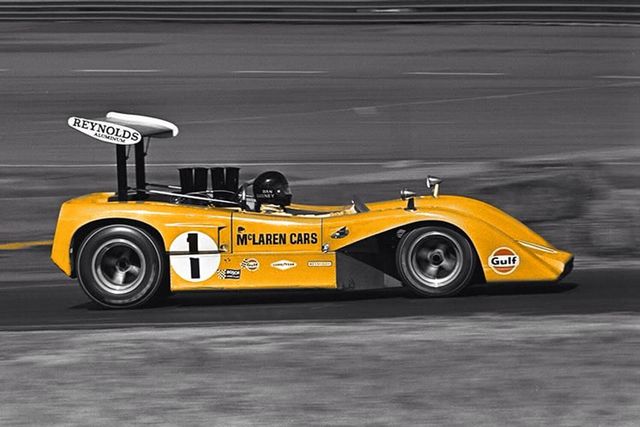

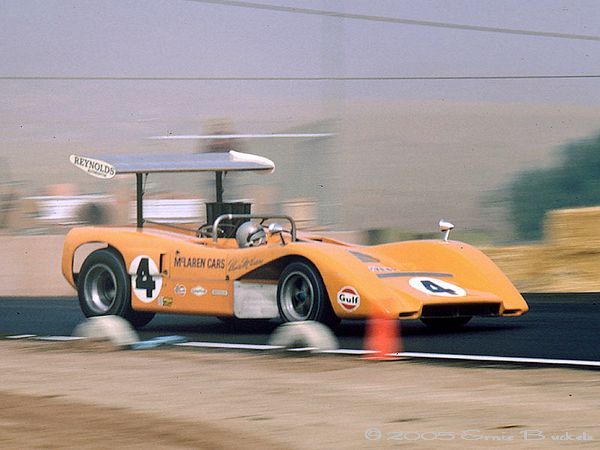

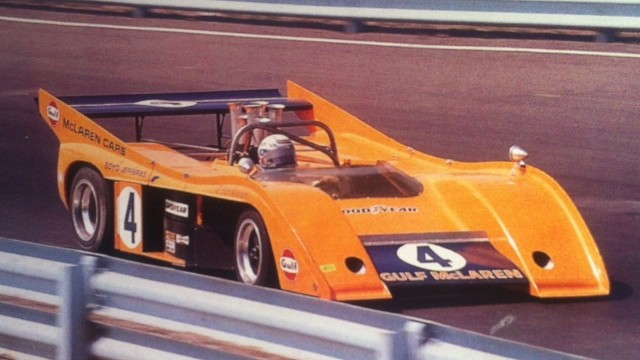

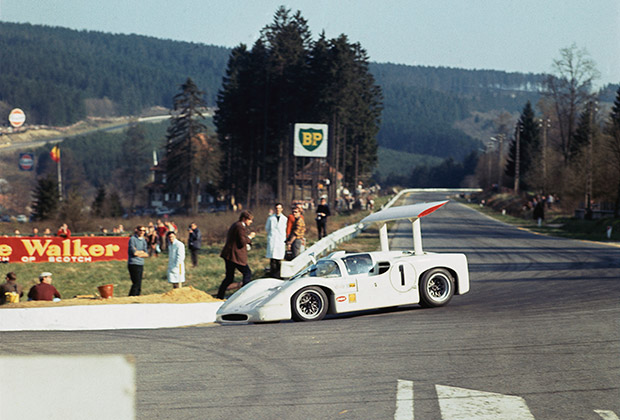

Spa 1000 Kilometers, 1967. The Phil Hill/Mike Spence Chaparral 2F Chevrolet 427 started from the pole but DNF due to gearbox issues. 1. Jacky Ickx/Dr. Dick Thompson (Mirage M1 Ford). 2. Jo Siffert/Hans Herrmann (Porsche 910). 3. Richard Attwood/Lucien Bianchi (Ferrari 412 P). Laguna Seca Can-Am, 1970. Vic Elford put the No. 66 Chaparral 2J Chevrolet on the pole by 1.8 sec. over the vaunted team McLaren machines, but failed to start because of engine problems. The pioneering ground effects concept for the Chaparral 2J originated at Chevrolet Engineering, and it was co-developed by GM engineers and Jim Hall.

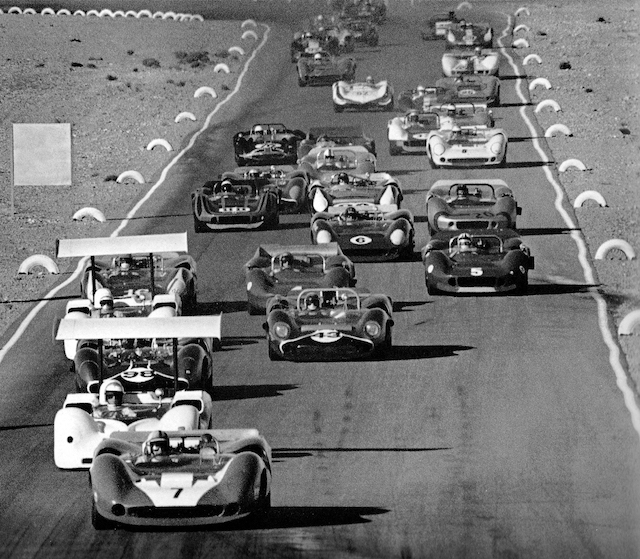

Laguna Seca Can-Am, 1970. Vic Elford put the No. 66 Chaparral 2J Chevrolet on the pole by 1.8 sec. over the vaunted team McLaren machines, but failed to start because of engine problems. The pioneering ground effects concept for the Chaparral 2J originated at Chevrolet Engineering, and it was co-developed by GM engineers and Jim Hall.