By Peter M. DeLorenzo

Detroit. Some of my colleagues have chastised me for my "Fumes" columns of late, suggesting that I dwell too much on racing's past and that it is somehow irrelevant in the Big Picture of things in the racing world as it stands today. It has also been suggested that I don't appreciate what's going in racing on today, which couldn't be further from the truth. I don't share that perspective, obviously.

I certainly appreciate the driving talent and the innovative technical minds in today's racing, and I've often written about it. I have often commented that NASCAR has some of the most creative minds and driving talent in the world, but that the series is continually hamstrung by the lack of leadership emanating out of Daytona Beach. That's all supposed to be fixed, and substantive changes are said to be coming fast and furiously to this form of motorsport that's well and truly on the ropes, but given NASCAR's track record, I am just going to relegate those promises to the "It Won't Be Long Now" File, and it will be a giant "we'll see" until further notice.

As for contemporary motorsport, I think Formula 1 needs an enema because it has become borderline unwatchable. And I have no confidence that the powers that be who are charged with the task with the next-gen regulations will be able to balance the burgeoning "green-tinged" perspectives with the need for real racing with visceral appeal. I really like what IMSA has done with American sports car racing but I do not like the WEC version of the sport. At all. The French have an uncanny knack to mess things up, and judging by what I've seen of late, that's not likely to change anytime soon. And I like IndyCar, although my disgust with temporary street circuits hasn't ebbed one bit. And for the record, I think Scott Dixon is one of the greatest drivers the sport has ever seen, and that's across all disciplines and series too.

I think a lot of contemporary racing has been swallowed up by the pursuit of money. No, of course that's not news, but just this week we saw Pato O'Ward, a potential future star talent, get sidelined out of an IndyCar ride due to the team's lack of resources. Yes, I know, thus it was ever so, but it still sucks and it's still the most distasteful side of contemporary racing. But then again, there are vintage racers with million-dollar budgets, so any chance of reducing the cost of going fast is slim, and none.

I do appreciate contemporary racing, but I am also a firm believer in that in order to know where you want to go, you have to understand where you've been. Historical context is important, no matter what arena you're in. With my presence on twitter (@PeterMDeLorenzo), I spend a lot of time reminding people about racing's past: the personalities, the giants, the tracks, the series, etc., etc. And much to my surprise, it has become very popular. I often receive comments about the memorable moments in racing that first captured the imagination of now lifelong fans. And it never gets old. So, I thought I'd share one of mine today...

My brother Tony (before he was a famous Corvette driver) and I and some friends traveled to the famous and now long gone Meadowdale Raceway back in August of 1964 to see the USRRC series (United States Road Racing Championship) race weekend, which was the pinnacle of American road racing at the time. This was the first professional road racing I had ever seen in person, and it was Tony's second (he had been to Meadowdale the year before). The USRRC race weekends consisted of a GT race (Corvettes and Cobras, etc.) as the opener, followed by the big sports cars (Chaparral, Cooper, etc.) as the feature.

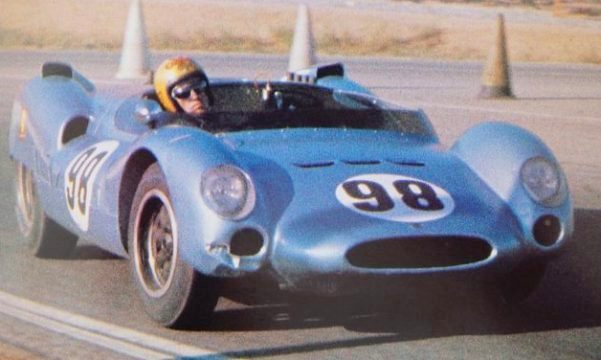

We watched as the factory Shelby American Cobra team led by Ken Miles (No. 98) and Bob Johnson (No. 99) dominated the GT field, finishing 1-2, followed by three independently-entered Cobras. The best Corvettes in the country were there and they were utterly humiliated, not only racing seconds a lap off of the pace, but none of them finished. Then something fascinating happened. We watched as the crack Shelby American crew swarmed over Miles' Cobra immediately following the GT race. They took the full windshield off, replacing it with a tiny plexiglass bubble windscreen, put fresh tires on it, filled it up with racing gas, and rolled it to the very back of the USRRC sports car race grid in 27th position. Dead last. It seems that the officials had allowed the team to enter Miles in the race with no qualifying time.

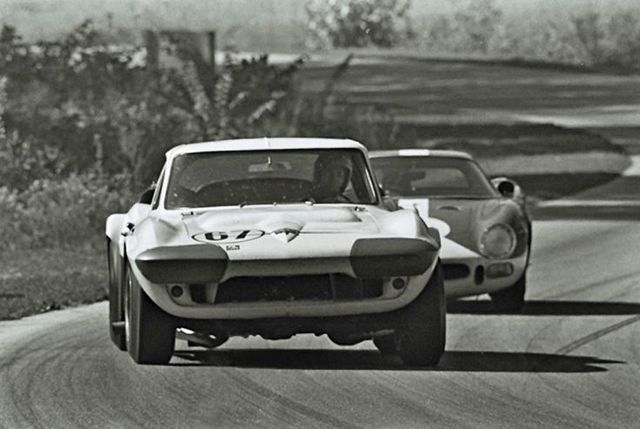

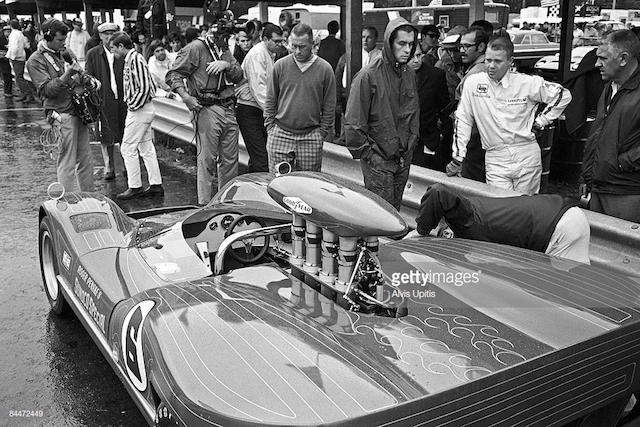

We were then treated to one of the most dazzling displays of race driving we had ever seen, and it still resonates to this day. Jim Hall (No. 66 Chaparral 2A Chevrolet) dominated the race, followed by his now-legendary teammate, Roger Penske (No. 67 Chaparral 2A Chevrolet) for a memorable 1-2 for the Texas Road Runners. Dick Doane (No. 29 McKee Chevette Mk 1 Chevrolet) finished third (sound familiar? Chevrolet would buy the rights to the Chevette name from McKee for the production car of the same name), and George Wintersteen (No. 12 Cooper Monaco T61M Chevrolet) finished fourth. And Mr. Miles? He would charge from the back of the field in a jaw-dropping run that would see him finish fifth - in his 289 Cobra - just one lap behind the winners. Believe me, this isn't a case of appreciating something from the past more now. No, we appreciated what we were seeing, in real time. It was simply fantastic and amazing, in the true sense of that overused word.

There's a lot to learn through historical context, I just wish more people involved in contemporary racing would spend a bit more time learning about it and taking lessons from it.

And that's the High-Octane Truth for this week. (Photo by John McCollister/Courtesy of RacingSportsCars.com)

(Photo by John McCollister/Courtesy of RacingSportsCars.com)

After dominating the GT race during the USRRC race weekend at Meadowdale Raceway in August of 1964, Ken Miles rolled his No. 98 Shelby American Cobra in position at the very back of the USRRC sports car feature race grid, in 27th position. Dead last. Miles would charge from the back of the field in a jaw-dropping run that would see him finish fifth overall, just one lap behind the winners.

MEMORABLE MOMENTS.

ORCHESTRATED INSANITY.

By Peter M. DeLorenzo

Detroit. When it comes to the ongoing train wreck/crash-fest that has come to define NASCAR on its biggest stage, there's no point in sugarcoating what went on in the Daytona 500 on Sunday. I have read the social media posts by the NASCAR apologists and other assorted fanboys (some even masquerading as journalists), and it's clear to me that they were watching an entirely different race than I was, because I needed a shovel to wade through the superlatives bandied about concerning a race that was nothing short of another flat-out embarrassment for NASCAR.

Here's a neat summation of the race: Start. Drone on. Pit stops. Drone on. Pit stops. Then continue droning on until Lap 190. Then it's run, crash, run, crash, red flag, run, crash, red flag, overtime, checkered flag. Done. And they deign to call this "The Great American Race." Really? I'd say a more accurate moniker would be "The Great American Shit Show." There is no excuse for the orchestrated insanity that NASCAR puts on for its biggest race. It is not compelling, nor is it riveting. Instead, watching the inevitable carnage unfold and the millions of dollars in equipment relegated to the scrap heap has become excruciatingly tedious and predictable. And once again the people who actually force themselves to watch are left to hope everyone involved in the inevitable "big one" is okay.

There are talking points being floated around by the NASCAR Media Manipulation Machine that this Daytona 500 will be the last race with the "old" restrictor plates and that from here on the racing will be positively improved due to a new rules package (including a new tapered restrictor plate) coming into play with next weekend's race at Atlanta. But the notion that everything will be instantly fixed like flipping a switch is incredibly naive.

The glacier pace with which the NASCAR brain trust moves is simply stupefying at this point. Remember, despite the fact that the "stick and ball" media still thinks NASCAR is the only form of racing currently in operation in the U.S., this racing series has been on a downward spiral for going on twelve years now. Many of the major high-dollar sponsorships have dried up, the in-person attendance continues its decline, the TV ratings do the same, and because of that the current presenting sponsor of the series - Monster Energy - was able to acquire the deal for $0.20 on the dollar in a fire sale.

Yet, what was all the buzz at Daytona? That the "Gen 7" car coming in 2022 will be really something. In fact, the "Gen 7" version of NASCAR itself is said to be dramatically reinvented, and that a radical redo of the way NASCAR goes about its business will come to the fore. But let's think about that for a moment. I don't care how radical the transformation is for the future of NASCAR, because we have three more seasons of the most ridiculous schedule in all of sports, the repetitive visits to the same tracks, and the relentless tedium of a series whose prime has long since passed to look forward to.

Same as it ever was, unfortunately.

It's hard for the people directly involved in NASCAR - and their auto manufacturer chief enablers - to step away from the series and look at it from an outsider's perspective. You can tell that because much of the happy talk emanating from Daytona revolves around the hackneyed phrase "it won't be long now!"

And that's really too bad, because it will be a long, long time from now. Three years in fact. And there's a real question as to whether or not NASCAR can survive that long in its present guise.

And that's the High-Octane Truth for this week. (Photo by Brian Lawdermilk/Getty Images)

(Photo by Brian Lawdermilk/Getty Images) (Ford Racing archives)

(Ford Racing archives)

Daytona, February 27, 1966. Cale Yarborough (No. 27 Banjo Matthews Abingdon Motor Company Ford) finished second to Richard Petty (No. 43 Petty Enterprises STP Plymouth GTX) in the Daytona 500. David Pearson (No. 6 Cotton Owens Southeastern Dodge Dealers Dodge) finished third.

ON RACING.

By Peter M. DeLorenzo

Editor's Note: Since the racing season is upon us and it's 3:00 a.m. somewhere, I conducted this interview with The Autoextremist concerning his current thoughts about racing. Enjoy. -WG

Detroit.

WG: So, what are you most interested in seeing this year?

PMD: I will watch a little bit of everything. My preference is road racing so the IMSA races and Indy cars on the road courses take precedence. And the two NASCAR road races are still worth watching. One qualifier: except for Monaco, I don't care for street courses, because you Can't See Shit when you're there. Saying that, I will probably take in most of the INDYCAR season, especially the Indianapolis 500.

WG: No F1 except Monaco?

PMD: I'll watch a few races here and there, especially Spa. But generally, F1 holds little interest for me. The cars are devoid of grace, the engines lack visceral appeal, and too many of the races are over by the first corner. I appreciate the effort and talent of all involved but I'm afraid of where F1 is going, especially with how the new rules package is - or isn't - coming together. I am not optimistic that the powers that be will make the right calls.

WG: And?

PMD: My absolute favorite form of motorsport to watch remains MotoGP. The sheer artistry and talent of those riders is simply incredible to behold.

WG: Is there any hope for NASCAR?

PMD: I think I've said enough about NASCAR already this year. With the new "Gen 7" NASCAR still three seasons away, however, I'm afraid that NASCAR's dire straits will only get worse. I understand that there's an all-hands-on-deck push going on with everyone directly involved with NASCAR to make this "Gen 7" idea a real transformational thing - with more short tracks, more road races, a shortened schedule, etc. - but they're running out of time. And meanwhile it's the same ol' same ol' for Three. More. Years. Ugh.

WG: What is the biggest challenge facing racing right now? Will it survive?

PMD: I would say relevance but that really isn't accurate. With the massive push into electrification by the world's automakers - and the equally massive efforts surrounding climate change - racing will come under more scrutiny by the hour. The FIA's response was to create Formula E, but I'm sorry, because the visceral appeal is nonexistent for me. I think that in order for racing to survive, relevance to our production vehicles will not be the answer. I've said this before and I'll say it again, going to see races will become an event where you can see - and hear - machines that we can't see and hear anymore on the streets. I am talking way down the road here, but still, racing will be put right to the edge.

WG: What about the Hydrogen Electric Racing Federation idea?

PMD: I still believe in the efficacy of it. Talk to any of the manufacturers involved in future vehicle development and they all agree on one thing - electric vehicles powered by hydrogen fuel cells will eventually replace BEVs. HERF would have accelerated development of these vehicles by a decade in my estimation, but at the time we proposed it (January 2007) the Great Recession was less than a year away, and the manufacturers that showed the most interest (GM and Toyota) simply couldn't put the project on their front burners. It's too bad, but I remain a True Believer in the concept.

WG: What is the one thing you'd like to say to the readers about the 2019 racing season?

PMD: I know a lot of our readers our avid racing enthusiasts, so I really don't have to say this, but for those who haven't gone to a race for a while, you should make the effort to do so. Whatever form of racing you enjoy, it is always better in person. TV gives us fantastic access, but you don't get the visceral feeling in your gut.

And that's the High-Octane Truth for this week. Elkhart Lake, Wisconsin, August, 1969. Jo Siffert in the No. 0 Porsche Audi Porsche 917 PA during practice for the Road America Can-Am. He qualified in eighth position but did not finish due to a blown engine.

Elkhart Lake, Wisconsin, August, 1969. Jo Siffert in the No. 0 Porsche Audi Porsche 917 PA during practice for the Road America Can-Am. He qualified in eighth position but did not finish due to a blown engine.

ON RACING.

Editor's Note: Due to popular demand, we're leaving Peter's column up for another week. He'll return with a new "Fumes" next week. -WG

By Peter M. DeLorenzo

Editor's Note: Since the racing season is upon us and it's 3:00 a.m. somewhere, I conducted this interview with The Autoextremist concerning his current thoughts about racing. Enjoy. -WG

Detroit.

WG: So, what are you most interested in seeing this year?

PMD: I will watch a little bit of everything. My preference is road racing so the IMSA races and Indy cars on the road courses take precedence. And the two NASCAR road races are still worth watching. One qualifier: except for Monaco, I don't care for street courses, because you Can't See Shit when you're there. Saying that, I will probably take in most of the INDYCAR season, especially the Indianapolis 500.

WG: No F1 except Monaco?

PMD: I'll watch a few races here and there, especially Spa. But generally, F1 holds little interest for me. The cars are devoid of grace, the engines lack visceral appeal, and too many of the races are over by the first corner. I appreciate the effort and talent of all involved but I'm afraid of where F1 is going, especially with how the new rules package is - or isn't - coming together. I am not optimistic that the powers that be will make the right calls.

WG: And?

PMD: My absolute favorite form of motorsport to watch remains MotoGP. The sheer artistry and talent of those riders is simply incredible to behold.

WG: Is there any hope for NASCAR?

PMD: I think I've said enough about NASCAR already this year. With the new "Gen 7" NASCAR still three seasons away, however, I'm afraid that NASCAR's dire straits will only get worse. I understand that there's an all-hands-on-deck push going on with everyone directly involved with NASCAR to make this "Gen 7" idea a real transformational thing - with more short tracks, more road races, a shortened schedule, etc. - but they're running out of time. And meanwhile it's the same ol' same ol' for Three. More. Years. Ugh.

WG: What is the biggest challenge facing racing right now? Will it survive?

PMD: I would say relevance but that really isn't accurate. With the massive push into electrification by the world's automakers - and the equally massive efforts surrounding climate change - racing will come under more scrutiny by the hour. The FIA's response was to create Formula E, but I'm sorry, because the visceral appeal is nonexistent for me. I think that in order for racing to survive, relevance to our production vehicles will not be the answer. I've said this before and I'll say it again, going to see races will become an event where you can see - and hear - machines that we can't see and hear anymore on the streets. I am talking way down the road here, but still, racing will be put right to the edge.

WG: What about the Hydrogen Electric Racing Federation idea?

PMD: I still believe in the efficacy of it. Talk to any of the manufacturers involved in future vehicle development and they all agree on one thing - electric vehicles powered by hydrogen fuel cells will eventually replace BEVs. HERF would have accelerated development of these vehicles by a decade in my estimation, but at the time we proposed it (January 2007) the Great Recession was less than a year away, and the manufacturers that showed the most interest (GM and Toyota) simply couldn't put the project on their front burners. It's too bad, but I remain a True Believer in the concept.

WG: What is the one thing you'd like to say to the readers about the 2019 racing season?

PMD: I know a lot of our readers our avid racing enthusiasts, so I really don't have to say this, but for those who haven't gone to a race for a while, you should make the effort to do so. Whatever form of racing you enjoy, it is always better in person. TV gives us fantastic access, but you don't get the visceral feeling in your gut.

And that's the High-Octane Truth for this week.

(Dave Friedman photo)

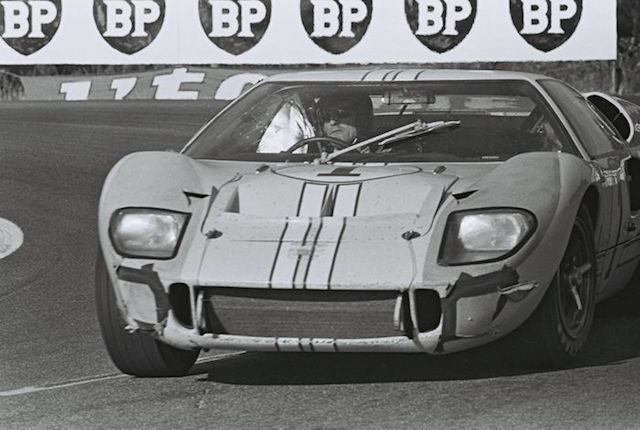

12 Hours of Sebring, March 26, 1966. The pole-winning No. 2 Shelby American Ford Mk II of Dan Gurney/Jerry Grant at speed. The big 427 cu. in. Ford wouldn't turn over for the Le Mans start, so Gurney was forced to start dead last. But he passed 27 cars on the first lap and by lap 44 he set a new lap record that was faster than his pole time, and he swept into the lead, passing Ken Miles in the No. 1 Shelby American Ford Mk II X-1 roadster. Gurney and co-driver Jerry Grant led the rest of the way, while Miles and co-driver Lloyd Ruby ran in second position. In a wild end to the race, Gurney's engine blew on the last lap within sight of the finish line, so he proceeded to push his car over the line. He was immediately disqualified for that rules infraction, however, and Miles/Ruby won the race.

THE NASCAR CONUNDRUM.

By Peter M. DeLorenzo

Detroit. No, this isn't another column criticizing NASCAR. At this point all racing enthusiasts should want NASCAR to succeed because if it continues to deteriorate, make no mistake, all racing will suffer in this country. NASCAR is so much a part of the industry of racing in this country that to see it slide is alarming to everyone involved, and it should be alarming to everyone who loves racing, because it will negatively affect the sport.

The new "Gen 7" car and associated other developments underway in Charlotte and Daytona are marked by intensive discussions and planning, and the "new" NASCAR will truly be something different to behold, and on many levels too. The design and engineering of the car, the schedule, the tracks, the length of races - everything is under review, and judging by what I'm hearing everything about the sport will be altered in some way. And though long overdue, this will be significant.

But in the midst of all of this upheaval, a conundrum looms over the powers that be in NASCAR. And it is this: The balance between racing and entertainment. In recent years, there is no question that NASCAR has swung the pendulum too far in the direction of entertainment. I actually dubbed it "racertainment" many years ago, and it really turned countless people off, both hard-core fans and racing enthusiasts alike.

And this gets to the heart of the matter, because in order to right the NASCAR ship, it will require a fundamental shift in philosophy. Equalized competition, meaning, the notion of making everything scrupulously equal, right down to the last lug nut, has killed the character of the sport and strangled the life out of NASCAR. It's a simple fact of the matter that NASCAR's relentless zeal to equalize the competition has left little or no breathing room - for anyone.

As I've said in many, many, previous columns, there have always been the "haves" and the "have-nots" in racing. It has been that way since racing began and it will be that way for the foreseeable future. So, while the powers that be wrestle with the new "Gen 7" NASCAR, they need to step back and carefully consider the way they go about their racing. I sincerely hope they alter that fundamental philosophy of equalized competition. It is okay to have front runners, mid-pack heroes and teams trying to get their footing in the top-level of NASCAR. In fact, it will be more interesting for everyone involved, especially for the enthusiasts who love racing.

And that's the High-Octane Truth this week. Daytona International Speedway, February, 1969. The beautiful No. 6 Sunoco Lola T70 Mk.3B GT Chevrolet entered by Roger Penske for Mark Donohue and Chuck Parsons during practice for the Daytona 24 Hours. Donohue qualified the machine in second position, and he and Parsons went on to win the race by 30 laps. Ed Leslie/Lothar Motschenbacher (No. 8 American International Racing Lola T70 Mk.3 GT Chevrolet) finished second, and Jerry Titus/Jon Ward (No. 26 Jon Ward Racing Ent. Pontiac Firebird) finished third overall and first in Touring 5.0.

Daytona International Speedway, February, 1969. The beautiful No. 6 Sunoco Lola T70 Mk.3B GT Chevrolet entered by Roger Penske for Mark Donohue and Chuck Parsons during practice for the Daytona 24 Hours. Donohue qualified the machine in second position, and he and Parsons went on to win the race by 30 laps. Ed Leslie/Lothar Motschenbacher (No. 8 American International Racing Lola T70 Mk.3 GT Chevrolet) finished second, and Jerry Titus/Jon Ward (No. 26 Jon Ward Racing Ent. Pontiac Firebird) finished third overall and first in Touring 5.0.

SPORTS CAR RACING IN A VACUUM.

By Peter M. DeLorenzo

Detroit. The 12 Hours of Sebring happened last weekend and a good time was had by all. A huge crowd, two big races (IMSA and WEC) and enough breathless commentary from the TV hosts to last a lifetime. So, it was all good, except there seemed to be something missing. But more on that in a minute.

The 1,000 Miles of Sebring WEC show was Friday afternoon running into the late evening. But the fact that the French in the FIA and ACO refuse to put a major North American endurance race on their schedule remains an insult that keeps festering. Lest you forget, Sebring and Daytona were once part of the international sports car racing calendar, but now the brainiacs in the WEC barely acknowledge American sports car interests, instead implying by their condescending actions that IMSA is somehow second class.

And how or why does the FIA get away with this? By holding out access to the 24 Hours of Le Mans for IMSA competitors, dictating who will be allowed to participate in the French endurance classic. So, IMSA bends over backwards to acquiesce to the FIA's wishes. Ironically enough, for years the major factory teams competing in the 24 Hours of Le Mans would test at Sebring, sometimes the week immediately after the running of the 12 Hours, because they discovered that running a 12-hour test at Sebring was more than equivalent to running 24 hours at Le Mans. The simple fact guiding these teams that would make them test at Sebring was that if something was going to break on a car, you would find that out in a hurry on the bone-crushing track surface in central Florida.

I know that some view this perspective as a waste of time given the fact that the ship has sailed on all of this, but seeing normally intelligent and savvy racing people "going along to get along" when it comes to the FIA lording over American racing interests is glaringly reprehensible. IMSA should have told the FIA/ACO that if they wanted to bring their show to Sebring they would be happy to accommodate them as part of the 12 Hours of Sebring, as long as that meant that America's oldest and most prestigious endurance race would also be included as part of the international sports car racing calendar. But what actually happened? Sebring International Raceway was forced to go to great expense to create separate pits and a new pit lane to accommodate the WEC show. Pathetic doesn't even begin to cover it.

Enough about that. So, what about the 12 Hours of Sebring? The beginning of the race itself was marred by the rainy start behind the pace car, but that couldn't be helped. But once the field was released the racing was excellent for the most part. The GM Racing Cadillac-branded prototypes dominated the show, and the GTLM class staged its typically furious battle right to the end (see more racing coverage in The Line -WG).

But saying that, the same issues remain for IMSA, unfortunately. Tracking the separate classes and presenting them during the race is one of the most difficult challenges in broadcast television, and it never gets easier. (By the way, LMP2 is a joke, as in, why bother at all?) And unless you're deeply immersed in an endurance race, the tedium and droning on and on is a real negative. Although to be fair, endurance races aren't meant for the casual TV racing watcher.

Racing enthusiasts who appreciate sports car racing rightly praise the current IMSA WeatherTech SportsCar Series as the best road racing ever presented in this country based on strength of schedule, the number of manufacturers participating, and the overall high-caliber of the teams and high-quality of the racing. But - and there's always a but - you can bet that the TV ratings will be dismal, because the TV ratings for major league sports car racing can't even compete with NASCAR's moribund Xfinity Series, let alone other major league racing events, which is a real shame.

Racing in a vacuum seems to be IMSA's lot (and IndyCar's, too, for that matter, as I've said in previous columns). It certainly is not what the dedicated people in Daytona Beach, or the talented teams and drivers, or the manufacturers want, but it is an unfortunate reality nonetheless.

And that's the High-Octane Truth for this week. AVUS, Berlin, 1937. The stunning 43-degree North Curve banking at the AVUS circuit was made entirely of bricks and dubbed "the wall of death" because of its lack of guardrails. If a driver had trouble and went off, he went off - and out. The 1937 race held at AVUS did not count for the Grand Prix World Championship, so teams were allowed to enter streamlined cars, which were similar to the cars Mercedes-Benz and Auto Union were using for high-speed record attempts on the Autobahn. This race was run in two heats. While qualifying for the second heat, Luigi Fagioli pushed his No. 33 Auto Union Type C streamliner to the pole position with a time of 4 minutes and 8.2 seconds at an average speed of 174 mph, which was the fastest motor racing lap in history at the time. Imagine that, on those tires!! It wasn't exceeded until Tony Bettenhausen bettered it in qualifying for the 1957 Race of Two Worlds at Monza in Italy. It was also bettered by four drivers during the 1971 Indianapolis 500. Hermann Lang's average race speed in his Mercedes-Benz streamliner of 171 mph was the fastest road race in history for nearly five decades, and was not matched on a high speed circuit until the mid-1980s at the 1986 Indianapolis 500.

AVUS, Berlin, 1937. The stunning 43-degree North Curve banking at the AVUS circuit was made entirely of bricks and dubbed "the wall of death" because of its lack of guardrails. If a driver had trouble and went off, he went off - and out. The 1937 race held at AVUS did not count for the Grand Prix World Championship, so teams were allowed to enter streamlined cars, which were similar to the cars Mercedes-Benz and Auto Union were using for high-speed record attempts on the Autobahn. This race was run in two heats. While qualifying for the second heat, Luigi Fagioli pushed his No. 33 Auto Union Type C streamliner to the pole position with a time of 4 minutes and 8.2 seconds at an average speed of 174 mph, which was the fastest motor racing lap in history at the time. Imagine that, on those tires!! It wasn't exceeded until Tony Bettenhausen bettered it in qualifying for the 1957 Race of Two Worlds at Monza in Italy. It was also bettered by four drivers during the 1971 Indianapolis 500. Hermann Lang's average race speed in his Mercedes-Benz streamliner of 171 mph was the fastest road race in history for nearly five decades, and was not matched on a high speed circuit until the mid-1980s at the 1986 Indianapolis 500.

REAL RACING IS THE THING FOR INDYCAR.

By Peter M. DeLorenzo

Detroit. The first INDYCAR win by eighteen-year-old Colton Herta (see more in "The Line" -WG) was fun to watch for racing enthusiasts of all stripes. Though he benefited from a fortuitous caution period, there's no question that the young, mature-beyond-his-years, and talented Herta will be a force to be reckoned with in America's premier open-wheel series for years to come.

But that was just part of the story from the Circuit of The Americas in Austin, Texas. The bigger picture story from Texas was the kind of racing on display. We saw the talented field in INDYCAR actually having to drive the cars around the circuit. More than that, they were forced to grab the cars by the scruffs of the neck and slide them in order to hustle them around the fast, 20-turn, 3.41-mile natural-terrain road course. And it was simply spectacular to watch.

I'm sure the juxtaposition with F1 at COTA wasn't lost on anyone watching, either. Yes, the F1 machines are clearly faster at lapping the circuit, but it's the way those cars and drivers go about going fast that's the problem. F1 is a technical exercise to an extreme degree and it has its place, although as readers of this column know I have been soured on the F1 product for years. Watch the F1 cars lap at COTA or any other circuit and it becomes a tedious, soulless exercise that's difficult to watch. Everything about F1 is sterile and regimented, and if a driver deigns to get the least bit sideways it becomes a glaring mistake, and reason for great consternation, hand-wringing and raised voices from the announcers.

What's wrong with this picture? Well, everything from my perspective.

Technical exercises are fine up to a point, but just as the powers that be in F1 are wrestling with a new rules package for 2022, I am quite sure that they're missing the point. They are absolutely certain - with a huge dollop of arrogance thrown in for good measure - that if they reduce the technical superiority in F1 that it would be a sign of weakness and the wrong direction to pursue. When, in fact, just the opposite would be true. F1 needs to dial back its technical imperative from a "10" to about a "7" on the Autoextremist Racing Scale. The aero needs to be reduced dramatically, the direct linkage to production car technology has to be toned-down within reason, and the emphasis of the series clearly has to be put back into the drivers' hands.

The result would be the kind of racing that was on display at Circuit of The Americas by the stars of INDYCAR. Hardcore racers actually racing, driving the wheels off of their machines the entire way around the circuit, all race long. I wasn't pleased at the attendance - although short of 50,000 people, the massive COTA always looks empty - but true racing enthusiasts have to be pleased with what they were able to see from INDYCAR on Sunday. INDYCAR is definitely on the upswing, and we need that series to stand on the pedal hard and continue what it's doing, because it's working.

As for the powers that be in F1, they continue to look down on INDYCAR as an inferior product. That's their blind arrogance getting in the way of reality. The lessons learned from Texas will fall on F1's deaf ears, which is really a shame. But, on the other hand, I am extremely excited for the future of INDYCAR on this continent, because as long as real racing remains the thing, racing enthusiasts are going to be well-served.

And that's the High-Octane Truth for this week. (Photo by Chris Owens/INDYCAR)

(Photo by Chris Owens/INDYCAR)

INDYCAR put on a great show at the Circuit of The Americas on Sunday. (Photo by Dave Friedman)

(Photo by Dave Friedman)

Riverside International Raceway, December 1, 1968. Dan Gurney (No. 48 AAR Olsonite Eagle/Ford) on his way to the win by one full lap in the USAC Champ Car Series race. Gurney was dominant at Riverside in whatever car he raced in. Bobby Unser (No. 3 Bob Wilke Rislone Eagle/Ford) was second and Lloyd Ruby (No. 25 Gene White Mongoose/Ford) finished third.

THE BEST OF THE BEST.

Editor-in-Chief's Note: Do we ever get tired of looking at great racing cars? I sure hope not. Yes, we've looked at these before, but they're still great, and still worth another look. And since we get new enthusiast readers every week, I'm sure they will appreciate these photos too. -PMD

By Peter M. DeLorenzo

Detroit. Anyone who has grown up in and around the sport has developed a list of favorite racing cars from the time they were kids. It usually started along the way with favorite model building kits or slot car sets, but we all developed our favorites, which we've all added to over the years. I am no exception. As a matter of fact, my list is extensive and at times convoluted, and by no means is it meant to be some sort of be-all and end-all, but I'm going to throw it out here anyway. (Yes, everyone has their lists, so if you have favorites to add, feel free to do so in Reader Mail - WG)

This is going to be a rambling discourse, so bear with me (and it's Part I because I'm sure I'll forget a bunch of cars, so I'll continue this discussion another day). For starters, I loved the Mercedes-Benz 196R "streamliner" introduced in the 1954 season. To this day it is absolutely stunning in person. And from an earlier era, the Auto Union racing cars were fabulous, especially the mid-engine Type C.

I loved the classic early Porsche racing cars, of course, especially the coupe that ran at Le Mans in 1951 and of course, the little coupes that ran in the Panamericana race in Mexico (which heavily influenced the look of the original Audi TT street car). While I'm on Porsche, I loved the 917 (but surprisingly in the one-off psychedelic Le Mans livery, not the Gulf colors). The early 911 RSRs (particularly in IROC configuration) and the look - and especially the sound - of the current IMSA 911 RSR. I am skipping over countless cool Porsche racing cars, but I have to mention the all-conquering Porsche 917/30 raced in the 1973 Can-Am season by Mark Donohue, and my all-time favorite racing Porsche (designed by Ferdinand Piech, no less), the fabulous little 908/3 designed specifically for sprint events like the Targa Florio and the Nurburgring.

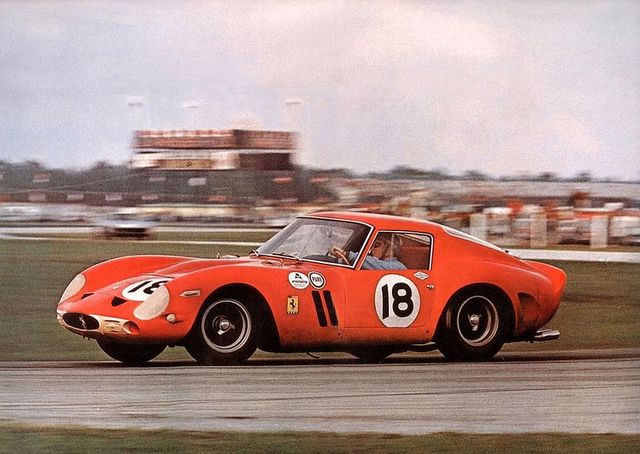

How can you not have a list without Ferrari? I loved the sports racing cars from the 50s, the Testa Rossa just being one of a long list of favorites. I loved the 156 "shark nose" F1 car, so elegant but provocative in its simplicity. And the GTO. But my all-time favorite racing Ferrari? The magnificent 330 P4 (the Penske Sunoco Ferrari 512M was spectacular, too, but the P4 does it for me).

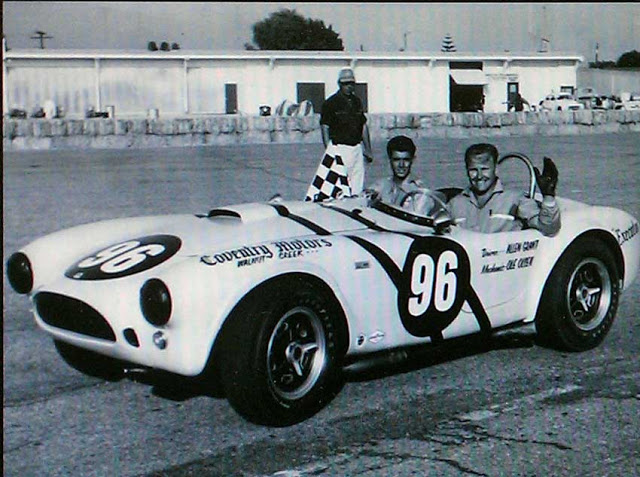

And then the Ford-powered racing machines. As readers know, the Shelby American Cobra is one of my all-time favorites, and I especially loved the early competition cars in all the myriad configurations, especially Ken Miles' favorite No. 98. And the perpetual favorite, the beautiful Peter Brock-designed Cobra Daytona Coupe. Then there are the short-lived but still great Ford-powered Cooper Monaco "King Cobra" sports racers from the early 60s, or the Shelby GT350 Mustangs (the car I learned to drive a stick with). And of course all of the Ford GTs and their variants, especially the 1967 Le Mans-winning Mark IV driven by Dan Gurney and A. J. Foyt (but I do love the original, unadorned Ford GT40 Mk 1 for its purity). Then there were the fabulous NASCAR Fords prepared by the Wood Brothers for Dan Gurney. And even the drag racing Ford Fairlane Thunderbolts, which were bad-assery to the first degree. And of course the Bud Moore Engineering Boss 302 Mustang Trans-Am cars.

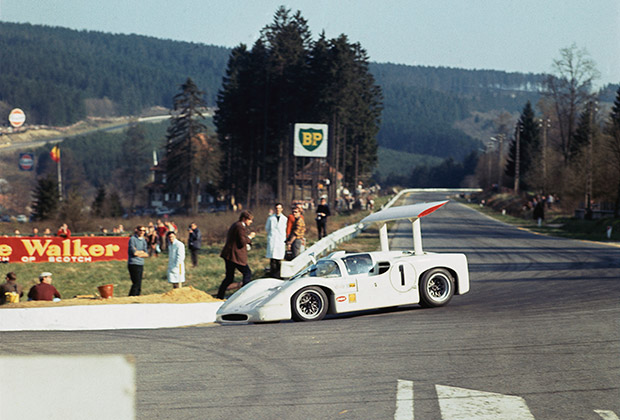

If anyone has followed me on twitter (@PeterMDeLorenzo) of late, I have been doing a historical tour of great racing cars and tracks in photographs, and it's no secret I reserve a special place in my heart for Jim Hall's fabulous Chaparral racing machines. I love all of them in all of the variations, but the 2E that Hall and Phil Hill dominated the Laguna Seca Can-Am weekend with in 1966 is right up there. I also loved the 2D and 2F coupes designed for endurance racing.

And I can't forget to mention the fabulous front-engine Scarab sports racers, built by Troutman and Barnes and powered by Chevrolet. Or the Bill Thomas Cheetah, which came to be just as the mid-engine revolution hit. Or the 1968 Penske Racing Trans-Am Camaro. (Yes, I know, the list goes on and on.)

The Corvette is always front and center when it comes to my favorite race cars. I loved the factory-developed 1957 Corvette SS, which appeared at Sebring, and the 1960 Briggs Cunningham Le Mans cars. And of course the fabulous Grand Sports - especially in John Mecom Racing Team Nassau livery - which have a visceral appeal that never gets old.

And, full disclosure, I loved the Owens/Corning Fiberglas Corvette Racing Team machines raced by my brother, Tony. The remarkable liveries of those machines, created by legendary GM design ace, Randy Wittine, were heavily copied and still resonate to this day. (I also preferred Randy's design for the Bud Moore Mustangs we purchased and campaigned in the 1971 Trans-Am season over the factory Butterscotch Yellow cars, and our OCF Trans-Am Camaros were beautiful too.) My favorite Corvette that my brother raced was the black 1968 "A" Production roadster that he won the June Sprints at Road America with (see below). This was right before the Owens/Corning sponsorship deal came together. And the current C7.R racers are fantastic, although not my favorite liveries by any stretch.

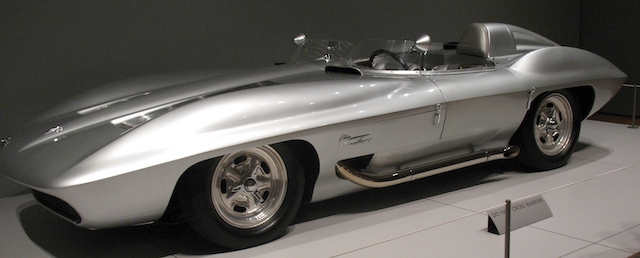

But my all-time favorite racing car is the original 1959 Corvette Sting Ray racer. GM Design icon Bill Mitchell purchased the leftover "mule" chassis from the Corvette SS program and enlisted some of the most talented designers at GM at the time - including a 19-year-old Peter Brock, who did the original sketch - to come up with the design language for the car. The result? Simply one of the most magnificent looking machines of all time. You really need to see the car in person to truly appreciate it.

I look forward to continuing this discussion. I haven't even covered the F1 cars, the Indy cars, the sports prototypes (Lola T70 Coupe, anyone?) and my other all-time favorite racing machines: the Team McLaren Can-Am cars.

And that's the High-Octane Truth for this week. The Mercedes-Benz 196R "streamliner."

The Mercedes-Benz 196R "streamliner."

The Auto Union Type D.

The Auto Union Type D. Dan Gurney in a Ferrari Testa Rossa, at Goodwood, 1959.

Dan Gurney in a Ferrari Testa Rossa, at Goodwood, 1959. The Troutman and Barnes Chevrolet-powered Scarab sports racer.

The Troutman and Barnes Chevrolet-powered Scarab sports racer. The Ferrari 250 GTO.

The Ferrari 250 GTO. Phil Hill in the Ferrari 156.

Phil Hill in the Ferrari 156. (Dave Friedman photo)

(Dave Friedman photo)

Dave MacDonald in the Cooper Monaco King Cobra Ford. (Dave Friedman photo)

(Dave Friedman photo)

Dan Gurney in the factory Shelby American Cobra roadster, Riverside, 1963.

(Dave Friedman photo)

(Dave Friedman photo)

The Shelby American Cobra Daytona Coupes at Le Mans, 1964. Phil Hill in the Chaparral 2E, Bridgehampton, New York, 1966.

Phil Hill in the Chaparral 2E, Bridgehampton, New York, 1966.

The 1959 Chevrolet Corvette Sting Ray racer.

The 1959 Chevrolet Corvette Sting Ray racer. Elkhart Lake, Wisconsin, June 1968. Tony DeLorenzo (No. 50 Hanley Dawson Chevrolet Corvette 427 L88) on his way to the win in the "A" Production feature at the June Sprints at Road America.

Elkhart Lake, Wisconsin, June 1968. Tony DeLorenzo (No. 50 Hanley Dawson Chevrolet Corvette 427 L88) on his way to the win in the "A" Production feature at the June Sprints at Road America.

GREAT CARS AND THEIR DRIVERS.

Peter M. DeLorenzo

Detroit. If you follow my twitter account (@PeterMDeLorenzo), you know that at times I present famous racing machines and the legendary drivers who wheeled them. Make no mistake, many of the contemporary stars in racing could have been great in any era, but there's no denying the fact that some of the most historic moments in the 50s, 60s and 70s still resonate for a lot of enthusiasts to this day. So for your consideration this week, we're presenting more great cars and the drivers who made them famous.

(Dave Friedman photo)

(Dave Friedman photo)

First of all, I neglected to post a picture of a Chevrolet Corvette Grand Sport last week, so here is a shot of Jim Hall (No. 67 Chevrolet Corvette Grand Sport) running ahead of Augie Pabst (No. 2 John Mecom Racing Zerex Ferrari 250 LM) out of Canada Corner during the Road America 500 in Elkhart Lake, Wisconsin, September 13, 1964.  (All American Racers)

(All American Racers)

Dan Gurney on his way to the win in the 1967 Belgian Grand Prix in the No. 36 All American Racers Eagle T1G Gurney-Weslake V12. Gurney's victory at Spa is the first and only time that an American citizen built and raced a car of his own construction and put it into the winner’s circle of a World Championship F1 race. Yes, there have been many beautiful open-wheel machines - the aforementioned Ferrari 156; Colin Chapman's Lotus 49-Cosworth; the McLaren-Ford MP4/8A; the McLaren M16C Indy car; Jim Hall's Chaparral 2K Cosworth Indy car; the All American Racers Indy cars, especially the Boundary Layer Adhesion Technology (BLAT) Eagle-Chevy, and on, and on, and on* - but for my money Gurney's beautiful midnight blue 1967 Eagle F1 machine, designed by Len Terry and constructed in Santa Ana, California, remains my favorite open-wheel car of all time and is still absolutely stunning in person. (*As you may have noticed, I have no contemporary open-wheel machines on my list. That's because - particularly in F1 - the cars are cold, devoid of beauty, emotionally un-involving and eminently forgettable.) (Dave Friedman photo)

(Dave Friedman photo)

Speaking of Lola, I think the T70 coupe is one of the most beautiful racing machines of all time. But if asked to pick one Lola over all of the many great ones, it would be the gorgeous No. 30 All American Racers Lola T70 Mk.2 - powered by a Gurney-Weslake 305 Ford - that Dan Gurney drove to victory in the second Can-Am race of the inaugural season for that legendary racing series, at Bridgehampton, New York, September 18, 1966.

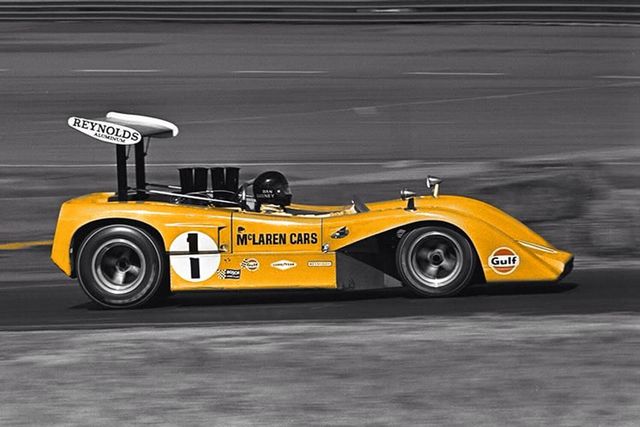

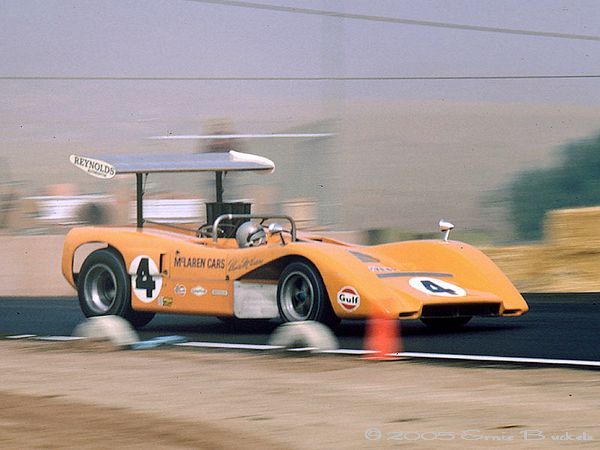

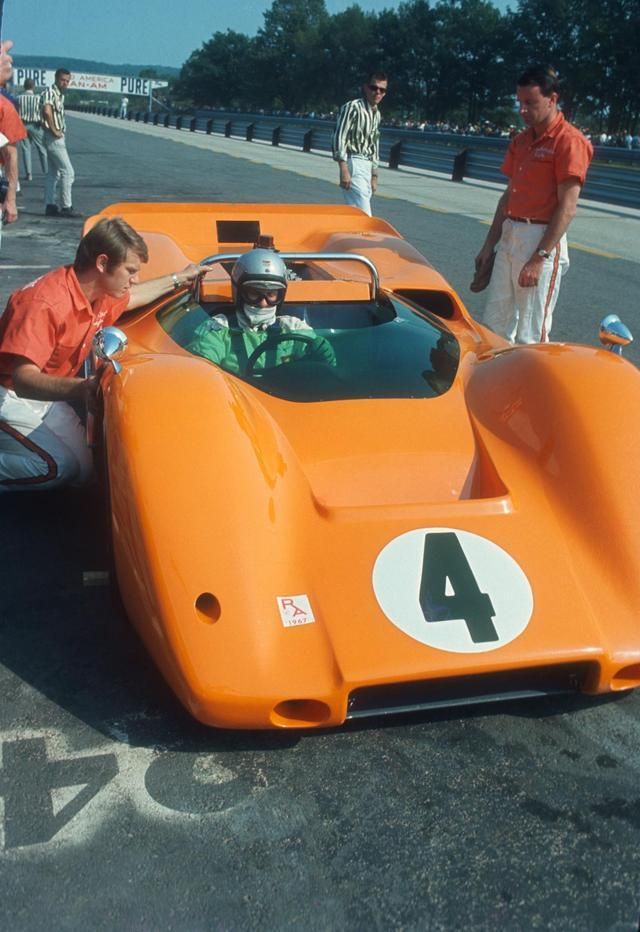

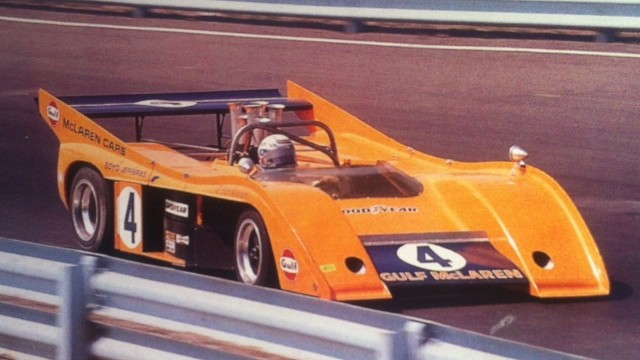

And I would be remiss if I didn't mention another group of my all-time favorite racing machines, those beautiful - and brutal - Can-Am machines from Bruce McLaren and McLaren Cars. I have five 1/18 scale racing car models on my desk currently (yes, I have a few more than that). Three Chaparrals (2C, 2E and 2F), a Porsche 910, and Dan Gurney's No. 1 McLaren M8B Chevrolet that he ran in the Can-Am at Michigan International Speedway in a guest drive. I was fortunate to see the Can-Am series in-period, and the kaleidoscope of great racing machines from that era deserves the term "legendary." Machines from Chaparral, Ferrari, Lola, Porsche and Shadow, along with a long list of "one-offs" are seared in my memory. To see - and hear - a Can-Am car flat-out at Road America was simply the best of the best racing experiences one could have. And I relish those experiences to this day. So following are a few classic images of the McLaren Can-Am machines.

Michigan International Speedway, 1969. Dan Gurney in the No. 1 McLaren M8B Chevrolet finished third behind teammates Bruce McLaren (No. 4 McLaren M8B Chevrolet) and Denny Hulme (No. 5 McLaren M8B Chevrolet) in a guest drive. (Photo by Pete Lyons)

(Photo by Pete Lyons)

Laguna Seca, California, 1968. Bruce McLaren (No. 4 McLaren M8A Chevrolet) during practice for the Can-Am.  (Photo by Pete Lyons)

(Photo by Pete Lyons)

Peter Revson on his way to the win in the Can-Am at Laguna Seca in his McLaren M8F Chevrolet, 1971.

(Pete Lyons)

Riverside International Raceway, 1968. Bruce McLaren (No. 4 Gulf/Reynolds Aluminum McLaren M8A Chevrolet), L. A. Times Grand Prix Can-Am.

Elkhart Lake, Wisconsin, 1969. Bruce McLaren (No. 4 Gulf/Reynolds Aluminum McLaren M8B Chevrolet) during practice for the Can-Am at Road America. (Pete Lyons photo)

(Pete Lyons photo)

Elkhart Lake, Wisconsin, 1967. Bruce McLaren in his No. 4 McLaren M6A Chevrolet - with Tyler Alexander - during practice for the Can-Am at Road America. (Pete Lyons photo)

(Pete Lyons photo)

Watkins Glen, New York, 1972. Peter Revson (No. 4 McLaren M20 Chevrolet) qualified on pole for the Can-Am but finished second to teammate Denny Hulme (No. 5 McLaren M20 Chevrolet) in the race.

Yes, I know, too many photos of the McLarens, but these were seminal machines emblematic of that run-what-you-brung era. Are there other favorite race cars? Absolutely. The Vanwall Grand Prix machine. The Jaguar D-Type. The Lotus 25 Grand Prix car. The Lotus-Ford Indianapolis cars, both the first machines in 1963 and Jim Clark's Lotus 38-Ford winner in 1965. Mario Andretti's John Player Special Lotus 78/79 F1 World Championship machines. Jackie Stewart's 1971 Lola T260 Chevrolet Can-Am car. The 2003 Le Mans-winning Bentley Speed 8. Andy Granatelli's 1967 STP Turbine Indy car driven by Parnelli Jones, and the updated "wedge" design turbine cars. As I said, the list goes on and on and on. I will cover more ground when I get to Part III, down the road.

And that's the High-Octane Truth for this week.

Spa Francorchamps, May 1, 1967. The No. 1 Chaparral Cars Chaparral 2F Chevrolet driven by Phil Hill and Mike Spence qualified on the pole for the Spa 1000 Kilometers but did not finish due to gearbox issues.

FAVORITE RACING CARS, CONTINUED.

By Peter M. DeLorenzo

Detroit. My list of favorite racing cars covers the gamut of the sport. What's fun is trying to distill a list of this kind down to a few, because it is damn-near impossible. There will always be more cars that you've forgotten about, so the list never gets old. So, presenting a few more this week for your viewing pleasure...

Designed by Vittorio Jano for Lancia in 1954, the Lancia D50 Grand Prix entry pioneered many significant innovations. For example, the engine acted as a stressed chassis member and it was also mounted off-center, which allowed for a lower overall height; and the pannier fuel cells were used for better aerodynamic performance and more balanced weight distribution. The D50 made its debut at the end of the 1954 Grand Prix season with two-time World Champion and Italian driving great Alberto Ascari behind the wheel. It was blistering fast right out of the box, but because the Lancia family was facing severe financial trouble, the Lancia family sold their controlling share in the Lancia company, and the assets of its racing team - Scuderia Lancia - were granted to Scuderia Ferrari. Although Ferrari continued to develop the car, many of Jano's most innovative design characteristics were removed. The car was first renamed as the "Lancia-Ferrari D50" but that was quickly dropped in favor of "Ferrari D50". Juan Manuel Fangio (above) won the 1956 World Championship driving the D50 for Ferrari. The D50s were entered in fourteen World Championship F1 Grands Prix, winning five.

Designed by Vittorio Jano for Lancia in 1954, the Lancia D50 Grand Prix entry pioneered many significant innovations. For example, the engine acted as a stressed chassis member and it was also mounted off-center, which allowed for a lower overall height; and the pannier fuel cells were used for better aerodynamic performance and more balanced weight distribution. The D50 made its debut at the end of the 1954 Grand Prix season with two-time World Champion and Italian driving great Alberto Ascari behind the wheel. It was blistering fast right out of the box, but because the Lancia family was facing severe financial trouble, the Lancia family sold their controlling share in the Lancia company, and the assets of its racing team - Scuderia Lancia - were granted to Scuderia Ferrari. Although Ferrari continued to develop the car, many of Jano's most innovative design characteristics were removed. The car was first renamed as the "Lancia-Ferrari D50" but that was quickly dropped in favor of "Ferrari D50". Juan Manuel Fangio (above) won the 1956 World Championship driving the D50 for Ferrari. The D50s were entered in fourteen World Championship F1 Grands Prix, winning five. (RM Sotheby's)

(RM Sotheby's)

The Jaguar D-Type is one of the most iconic racing cars ever built. Originally produced between 1954 and 1957, the Jaguar bristled with technical innovation heavily influenced by the aviation business. It featured monocoque construction and a sophisticated approach to aerodynamic efficiency. The Jaguar D-Type won the 24 Hours of Le Mans in 1955, 1956 and 1957. Jaguar is now producing 25 "continuation" D-Types, which will be priced at $1.4 million. I expect the prices for these continuation models to soar, especially since original D-Types now go for over $20 million.

(Grand Prix History)

(Grand Prix History)

The Lotus 25 revolutionized the design of open-wheel racing cars and fundamentally changed the sport. The mid-engined Lotus 25 was not the first racing car with a monocoque chassis, but its visionary design by Colin Chapman combined with the brilliance of Jimmy Clark resulted in phenomenal success. Clark won seven out of ten races and his first World Championship with the Lotus 25 in 1963.  (Ford Racing Archives)

(Ford Racing Archives)

Jimmy Clark (with Colin Chapman) in the Lotus 38-Ford during practice for the 1965 Indianapolis 500. He would win the race handily.

(Autosport)

Speaking of iconic racing machines, Mario Andretti won his World Championship in 1978 with the beautiful and highly innovative Lotus 79-Ford.

Parnelli Jones in the all-wheel-drive No. 40 STP-Paxton Turbocar machine dominated the 1967 Indianapolis 500 at will. Jones coasted to a stop with three laps to go because of a $6.00 transmission bearing failure. Innovation courtesy of Andy Granatelli, a man who never got enough credit for his vision.

Graham Hill in the No. 70 STP Lotus 56 Turbine machine at Indianapolis in 1968. Colin Chapman took the turbine power idea to heart and came up with a visionary car design of his own for the 1968 Indianapolis 500.

Mario Andretti's No. 11 Ford Fairlane "stock car" with which he stunned the NASCAR establishment by winning the 1967 Daytona 500. The 60s NASCAR machines were brutal, purposeful but beautiful in their own right.

Mario Andretti's No. 11 Ford Fairlane "stock car" with which he stunned the NASCAR establishment by winning the 1967 Daytona 500. The 60s NASCAR machines were brutal, purposeful but beautiful in their own right. I may have already mentioned this car, but Jackie Stewart's 1971 Carl Haas Racing L&M Lola T260 Chevrolet remains one of my favorite Can-Am machines of all time. I watched Stewart manhandle this evil handling machine, wringing every last drop of speed out of it while giving Team McLaren fits. It may have not been the prettiest of machines, but in Stewart's hands it was magnificent.

I may have already mentioned this car, but Jackie Stewart's 1971 Carl Haas Racing L&M Lola T260 Chevrolet remains one of my favorite Can-Am machines of all time. I watched Stewart manhandle this evil handling machine, wringing every last drop of speed out of it while giving Team McLaren fits. It may have not been the prettiest of machines, but in Stewart's hands it was magnificent.

Yes, another chapter of "Favorite Racing Cars" has come to a close. I could go on and I probably will in another chapter, because there are so many pivotal - and memorable - racing machines that writing about them never gets old.

And that's the High-Octane Truth for this week.

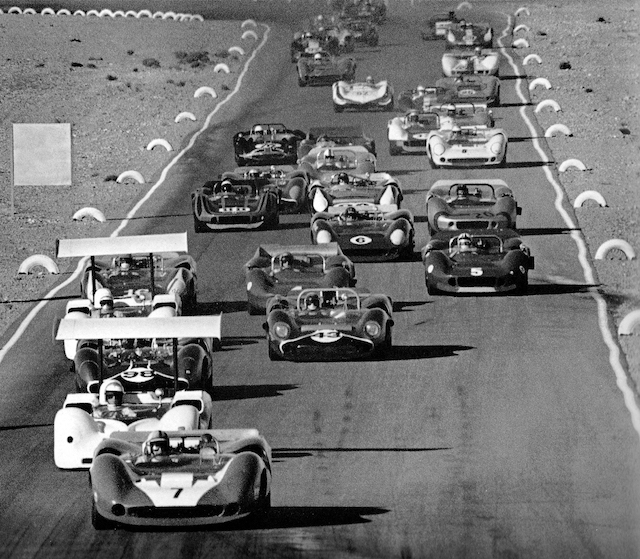

(Dave Friedman photo)

Las Vegas, Nevada, 1966. Talk about an all-star lineup. Early laps of the Stardust Grand Prix Can-Am race with John Surtees (No. 7 Team Surtees Lola T70 Mk.2 Chevrolet); Jim Hall (No. 66 Chaparral 2E Chevrolet); Parnelli Jones (No. 98 John Mecom Racing Lola T70 Mk.2 Chevrolet); Phil Hill (No. 65 Chaparral 2E Chevrolet); Jackie Stewart (No. 43 John Mecom Racing Lola T70 Mk.2 Chevrolet); George Follmer (No. 16 Lola T70 Mk.2 Chevrolet); Bruce McLaren (No. 4 McLaren Elva Mark II B Chevrolet); Chris Amon (No. 5 McLaren Elva Mark II Chevrolet) and Mark Donohue (No. 6 Penske Racing Sunoco Special Lola T70 Mk.2 Chevrolet). Results: 1. Surtees 2. McLaren 3. Donohue.

MORE FAVORITE RACING CARS.

Detroit. I get a lot of feedback about these "Favorite Racing Cars" columns, but one recurring question is ever-present: Does contemporary racing still hold my interest? Yes it does, but only up to a point. What's going on in the newly-invigorated IMSA WeatherTech SportsCar Championship is really exceptional. I still follow IndyCar closely, and MotoGP remains my favorite. The rest? It's just hit-and-miss for me, especially with F1, because the cars and the sanitized circus leave me cold. And there are still a few NASCAR races worth seeing, but then again, only a very few.

I've been doing these "Favorite Racing Cars" columns for a few weeks now, including Part I, Part II and Part III, and the response has been overwhelming, both here and on my Twitter feed (@PeterMDeLorenzo). Part of it has to do with enthusiasts of a certain age remembering what first grabbed them about the sport. Where they were, who they were with and what was seared in their memory about the machines when they had the opportunity to see them, not as vintage racers, but "in-period." And part of it has to do with the fact that machines of previous eras undeniably had more visceral appeal, both in terms of the diversity of the looks of the machines themselves, and the sounds they generated as well.

It's no secret that once technology started to swallow the sport whole, and the "spec" era of motorsport took hold, a lot of that visceral appeal was lost in translation. It is what it is, however, and the clock can't be turned back. Make no mistake, there are some stunning machines in contemporary motorsport as well, and I will get to them eventually. This week, I have no real pattern, just some random images of memorable racing machines in no particular order. I hope you enjoy it.

(Dave Friedman photo)

(Dave Friedman photo)Nassau, Bahamas, December, 1964. Ken Miles in the No. 98 Shelby American Cobra powered by a 390-cu. in. V8. It was blistering fast, but cooling was obviously an issue!

Monaco, 1967. Jim Clark (No. 12 Team Lotus 33/Climax) races ahead of Dan Gurney (No. 23 Eagle T1G/Weslake) during the Grand Prix of Monaco.

Monaco, 1967. Jim Clark (No. 12 Team Lotus 33/Climax) races ahead of Dan Gurney (No. 23 Eagle T1G/Weslake) during the Grand Prix of Monaco.  Circuit Mont-Tremblant, Quebec, Sunday, August 6, 1967. Bobby Unser in the No. 6 Rislone Eagle/Ford, during the USAC Champ Car race.

Circuit Mont-Tremblant, Quebec, Sunday, August 6, 1967. Bobby Unser in the No. 6 Rislone Eagle/Ford, during the USAC Champ Car race. Elkhart Lake, Wisconsin, 1960. The 1959 Chevrolet Corvette Sting Ray racer in its early red livery at Road America.

Elkhart Lake, Wisconsin, 1960. The 1959 Chevrolet Corvette Sting Ray racer in its early red livery at Road America. (Audi)

(Audi)The magnificent 1938 Auto Union Type D Grand Prix car.

The fabulous 1954 Mercedes-Benz 196R "streamliner" Grand Prix car photographed at the Petersen Museum in Los Angeles.

(Dave Friedman photo)

(Dave Friedman photo) (Dave Friedman photo)

(Dave Friedman photo)Allen Grant in the No. 96 Coventry Motors Cobra, 1963. That's a young George Lucas in the passenger seat. Yes, that George Lucas.

(Bondurant collection)

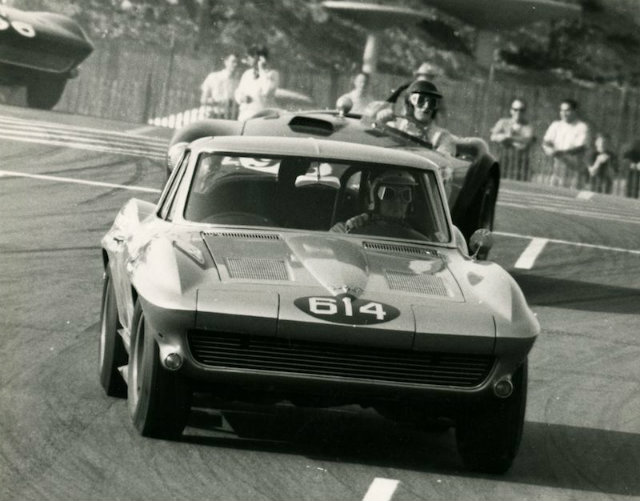

(Bondurant collection)Bob Bondurant (No. 614 Washburn Chevrolet Corvette Sting Ray) is pursued by Ken Miles (No. 298 Shelby American Cobra) in the Dodger Stadium sports car races in 1963.

(SportsCarDigest.com)

(SportsCarDigest.com)Bob Bondurant (No. 614 Washburn Chevrolet Corvette), Riverside, 1961.

(Dave Friedman photo)

(Dave Friedman photo)Elkhart Lake, Wisconsin, September, 1963. The Shelby American Cobra Racing Team transporter as it arrived at Road America for the 500-mile USRRC Race. Things were decidedly different back then...

LOOKING BACK WHILE LOOKING AHEAD.

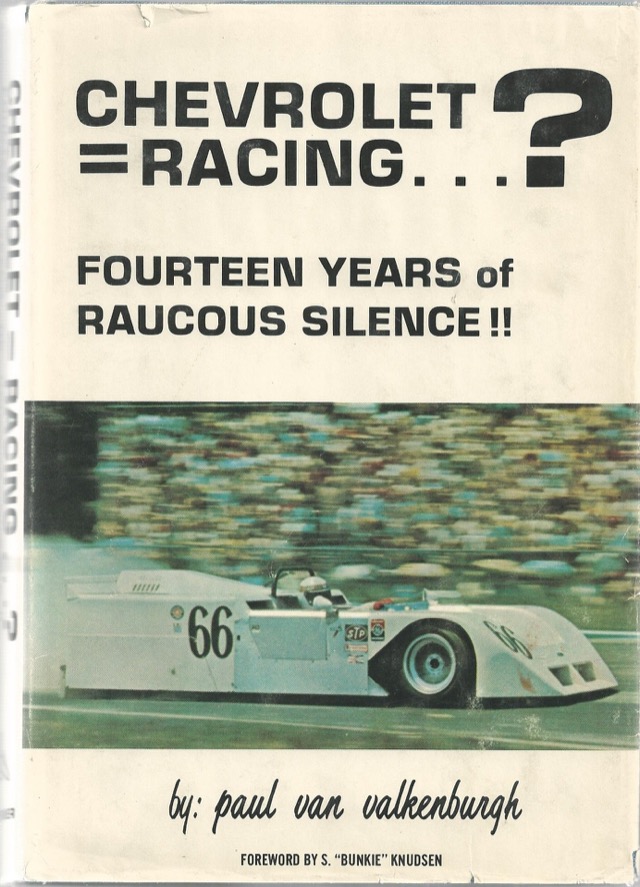

Editor's Note: The Chaparral Cars/GM relationship is an important historical milestone to take note of in American motorsports. Many enthusiasts are unaware of the extent of this relationship to this day. And Paul Van Valkenburgh's book deserves to be recognized for its incredible insider's perspective. Peter reprises both in his column this week. -WG

By Peter M. DeLorenzo

Detroit. As many readers know, I've written often in this space about the future of racing and the ramifications of a changing world on the sport. A previous column - "When All Racing Becomes 'Vintage' Racing" - was another in a long line of columns concerning the future of the sport. For people who love and are enthusiasts of the sport, and for people directly involved in the business of motorsport, the future should be of serious concern, and my reasons for writing about this subject on a continuous basis are well documented.

It's easy for the players in this sport, the team owners, drivers, technicians, etc., to get lost in the immediacy of what they do. Supporting a modern racing organization with the proper funding to retain talented employees while chasing sponsorship is a never-ending task, and it understandably must be a top priority. But while doing this it's easy to lose sight of the Big Picture because, after all, once a team's personnel and budgets are secured, overriding concerns about the overall health of a racing series become secondary.

But when a given racing series plays out before empty grandstands and excuses are continuously made about minuscule TV ratings, and the key players involved operate as if wearing blinders while insisting that everything is all good, this is what I call "racing in a vacuum." And it's a seriously myopic way to go about the business of racing, because to pretend that this is all going to continue on without repercussions and consequences is to display a level of naivete that almost defies understanding. Witness the Brian France remarks at Homestead-Miami Speedway last weekend, whereupon he insisted - yet again - that everything is good with NASCAR, which is flat-out laughable as even the most prominent NASCAR teams are struggling to find sponsors. Or the fact that the sport of Indy car racing is almost back where it started, which means that there's the Indianapolis 500 and a bunch of other races of varying degrees of substance making up the IndyCar Series schedule. Not to mention the glacial pace of change in F1, which has become a recurring joke, while the players argue about new engine rules for 2022.

I constantly prod and push the powers that be in this sport to get their heads out of their asses and take the long view, because if they fail to do so, racing will continue to fade in importance except for a few premier events, which would be a real shame.

If you follow me on Twitter (@PeterMDeLorenzo) you know that I've been posting images and commentary covering a lot of the compelling historical stories of racing's golden years. Of late I've focused on the story of the fabulous Chaparrals of Jim Hall, which marked one of the high points of "blue-sky" thinking and advanced technical developments in the sport. Through the course of my Twitter postings, one of my Twitter followers was incredulous to find out that Chevrolet was deeply involved in a technical partnership with Jim Hall, one that was completely kept under the table due to the fact that some of the suits on the famous 14th Floor of the GM Building were decidedly anti-racing.

Though I prefer the way Ford went about its racing in the 60s, which was part of an aboveboard, orchestrated marketing push called "Total Performance," the story of the Chaparrals and other racing endeavors by GM/Chevrolet Engineering's True Believers and Best and Brightest is one of the most fascinating stories in the history of motorsport. If you can get your hands on Paul Van Valkenburgh's vivid account of those incredible years - "Chevrolet = Racing...? Fourteen Years of Raucous Silence!!" - you will be amazed at the stories and photos documenting Chevrolet Engineering's deep involvement in the Chaparral program, and other racing forays with John Mecom, Roger Penske and a host of others.

The reason I'm bringing this up is that those fourteen years coincided with one of the most creative eras in motorsports history, long before the sport devolved into a maize of restrictions and specifications. I would like to think we can somehow muster a new era of creativity in racing again, but as long as "racing in a vacuum" is racing's standard operating procedure, I'm afraid the sport will continue spinning its wheels along the road to its inevitable decline.

And that's the High-Octane Truth for this week. (Amazon)

(Amazon)

"Chevrolet = Racing...? Fourteen Years of Raucous Silence!!" was Paul Van Valkenburgh's vivid account of GM/Chevrolet Engineering's under the table racing programs. A fascinating read. Elkhart Lake, Wisconsin, 1965. Hap Sharp in the No. 65 Chaparral 2A (with 2C modifications) drives through the paddock @roadamerica. The Chaparral team swept the Road America 500, finishing 1-2.

Elkhart Lake, Wisconsin, 1965. Hap Sharp in the No. 65 Chaparral 2A (with 2C modifications) drives through the paddock @roadamerica. The Chaparral team swept the Road America 500, finishing 1-2. The Corvette GSIIb was the Chevrolet Engineering research version of the Chaparral 2 and its iterations.

The Corvette GSIIb was the Chevrolet Engineering research version of the Chaparral 2 and its iterations.

Spa 1000 Kilometers, 1967. The Phil Hill/Mike Spence Chaparral 2F Chevrolet 427 started from the pole but DNF due to gearbox issues. 1. Jacky Ickx/Dr. Dick Thompson (Mirage M1 Ford). 2. Jo Siffert/Hans Herrmann (Porsche 910). 3. Richard Attwood/Lucien Bianchi (Ferrari 412 P). Laguna Seca Can-Am, 1970. Vic Elford put the No. 66 Chaparral 2J Chevrolet on the pole by 1.8 sec. over the vaunted team McLaren machines, but failed to start because of engine problems. The pioneering ground effects concept for the Chaparral 2J originated at Chevrolet Engineering, and it was co-developed by GM engineers and Jim Hall.

Laguna Seca Can-Am, 1970. Vic Elford put the No. 66 Chaparral 2J Chevrolet on the pole by 1.8 sec. over the vaunted team McLaren machines, but failed to start because of engine problems. The pioneering ground effects concept for the Chaparral 2J originated at Chevrolet Engineering, and it was co-developed by GM engineers and Jim Hall.

LOOKING BACK WHILE LOOKING AHEAD, PART II.

By Peter M. DeLorenzo

Detroit. In continuing my exploration of the history of motorsport, I'd like to point out that this isn't an exercise in dwelling in the past. I feel it's critically important to remember where we've been, before we can understand where we want to go. Many of my followers on Twitter (@PeterMDeLorenzo) are shocked to see some of the historical aspects of the sport for the very first time. They are discovering the rich legacy of the sport and how many ideas in racing have been done before, and to great effect.

One particularly shocking discovery for many enthusiasts was the AVUS circuit in Berlin, with its steeply banked (43°) North Curve made entirely of bricks.The daunting curve became known as the "Wall of Death," because there was no retaining barrier so cars that missed the turn easily flew off it and right out of the circuit. The 1937 race at AVUS did not count for the F1 World Championship, so non-GP cars were allowed. The factory German teams of Auto Union and Mercedes-Benz brought specially-built streamlined cars to contest the event. This race was run in two heats, and during qualifying for the second heat, Luigi Fagioli put his Auto Union Type C on the pole with a time of 4 minutes and 8.2 seconds at an average speed of 174 mph - which was the fastest motor racing lap in history at that time. And Hermann Lang pushed his Mercedes-Benz to an average race speed of 171 mph, which was the fastest road race in history for nearly five decades, and was not matched on a high speed circuit until the mid-1980s at the 1986 Indianapolis 500. Think about that for a moment. Incredible.

The lessons learned in the past will play an essential role in balancing the burgeoning technical demands of the sport, while at the same time not degrading the visceral appeal of the sport. This balancing act has, to me, become paramount. Yes, we are immersed in the shifting winds of a society that doesn't embrace motorsport as it once did, but still, if the powers that be don't come together to take the steps necessary that will ensure the sport's survival, then we have to embrace the real possibility that the sport will continue to get smaller, except for the few exceptional events.

That's the High-Octane Truth for this week.

(Sports Car Digest)

12 Hours of Sebring, March, 26, 1966. The Chaparral Cars team being pushed to their starting positions. The No. 11 Chaparral 2D Chevrolet was driven by Jim Hall/Hap Sharp, and the No. 12 Chaparral 2D Chevrolet was driven by Phil Hill/Jo Bonnier.

(Getty Images)

Enzo Ferrari looks on as American Richie Ginther prepares to take out the new Ferrari 156 for a run, 1961.

Scuderia Ferrari at the Monaco GP, 1961. Wolfgang von Trips (No. 40 Ferrari 156); Richie Ginther (No. 36 Ferrari 156); Phil Hill (No. 38 Ferrari 156). Stirling Moss (No. 20 Lotus-Climax) won that year, while Ginther was second and Hill, third.

AVUS, Berlin, 1937. Luigi Fagioli put his Auto Union Type C on the pole with an average speed of 174 mph, which was the fastest motor racing lap in history at that time.

Elkhart Lake, Wisconsin, August 31, 1968. Jim Hall (No. 66 Chaparral 2G Chevrolet) heads out for practice for the Road America Can-Am.

(Dave Friedman)

Indianapolis Motor Speedway, May 1963. Jim Clark, Colin Chapman and Dan Gurney looking over the back of Gurney's Lotus-Ford.

(Getty Images)

Elkhart Lake, Wisconsin, September 1968. Mark Donohue and Roger Penske stand by the No. 6 Sunoco McLaren M6B Chevrolet during Can-Am practice at road America. Mark finished third in the race.

Juan Manuel Fangio in the No. 18 Mercedes-Benz W196 streamliner on his way to victory in the 1955 Italian Grand Prix.

(Dave Friedman)

Elkhart Lake, Wisconsin, September, 1969. Jim Hall leans against his No. 7 Chaparral 2H Chevrolet, with John Surtees at the wheel. The 2H was a radical low drag concept Can-Am machine that proved to be Hall's only major disappointment in terms of building Chaparrals. The car was multiple seconds per lap slower than the quickest cars everywhere the car appeared. The car is stunning to look at in person to this day, but the reality is that car never worked as intended.

THE FASTEST 33.

By Peter M. DeLorenzo

Detroit. I have read the voluminous back and forth from all sides of the issue, but the bottom line for me - though Sunday's final bumping did prove to be dramatic - is that qualifying for the Indianapolis 500 is a mess. I appreciate the fact that people may think that because Fernando Alonso didn't make the field it validated the entire qualifying process, but it doesn't. The McLaren effort wasn't good enough and he wasn't fast enough and so be it - that part of it was fine. But again, the entire Indy 500 qualifications process has been messed with and watered down with gimmicks over the years, and we have arrived at this juncture where a reset is desperately needed.

First of all, the argument that there should be guaranteed spots in the field for the major teams is preposterous. Make no mistake, I appreciate the massive contributions that Roger Penske, Chip Ganassi, Michael Andretti and Bobby Rahal have made to the sport of major league open wheel racing in this country. They not only support the series, they underwrite payrolls for hundreds of professionals in this business, bring corporate partners to the sport, and generally provide the momentum for the sport of Indy car racing in this country to survive. Again, their contributions, both individually and collectively, are incalculable.

But, there are no guarantees in life, or in racing. If these racing juggernauts come undone in qualifying and can't make the field, it would be devastating to their sponsors and The Show, but life would go on. And they are of course free to come back the following year, sharper, better prepared and ready to make the field. That's how it should be. Guaranteed spots in the field would destroy the integrity of the entire event. Period.

As for the "Fast Nine Shootout" business, it's convoluted, gimmicky and stupid. Indianapolis needs to go back to the idea of establishing a field of "The Fastest 33" starters - in descending order of speed - with bumping to get into the field still allowed on the last hour of the last day of qualifications. "The Fastest 33" would restore integrity to the qualification process for the Indianapolis 500.

And it needs to happen in 2020.

And that's the High-Octane Truth for this week.

(Photo by Chris Owens/INDYCAR)

Simon Pagenaud delivered the eighteenth Indianapolis 500 pole position for Team Penske, extending the benchmark NTT IndyCar Series program's record that stands at thirteen more than any other team. In addition, Pagenaud became the first Frenchman in a century to capture the Indy 500 pole, since Rene Thomas in 1919.

(Photo by Chris Owens/INDYCAR)

The Front Row for the 2019 Indianapolis 500 presented by Gainbridge, the 103rd running of "The Greatest Spectacle in Racing." On pole (right): Simon Pagenaud in the No. 22 Team Penske Menards Chevrolet Turbo V6 with a four-lap average speed of 229.992 mph; Ed Carpenter will start from the middle of the front row in his No. 20 Ed Carpenter Racing Preferred Freezer Services Chevrolet Turbo V6 with a speed of 229.889 mph; and Spencer Pigot (No. 21 Ed Carpenter Racing Chevrolet Turbo V6) will start third with a speed of 229.826 mph. Pagenaud will lead the closest field in Indianapolis 500 history to the green flag. The time separating Pagenaud's four-lap qualifying attempt and that of slowest qualifier Pippa Mann was 1.8932 seconds, breaking the previous mark of 2.1509 seconds in 2014. The 228.240 mph speed average of the 33 qualifiers is fourth fastest in Indianapolis 500 history. The 103rd Running of the Indianapolis 500 airs live at 11 a.m. Sunday, May 26 on NBC and the Advance Auto Parts INDYCAR Radio Network.

Indianapolis Motor Speedway, May 1964. Dan Gurney and Jim Clark conversing during practice for that year's Indianapolis 500.

A RIVETING INDIANAPOLIS 500.

By Peter M. DeLorenzo

Detroit. Let's dispense with the usual gamut of negatives about the current state of IndyCar racing: It's a spec series with not enough engine manufacturers that struggles to gain a notable TV audience and suffers from a lack of in-person attendance as well. Add to that the notion that the Indianapolis 500 is somehow reduced in stature and you have a recipe for less-than-healthy major league open-wheel racing series. At least on paper. And although there is some truth to that roster of negatives, fortunately none of that was on display on Sunday.

The 2019 Indianapolis 500 was a riveting display of speed and strategy that made the other two racing events - the Monaco Grand Prix and the Coca-Cola 600 NASCAR race - absolutely pale in comparison. The Monaco Grand Prix was over in the first corner, and NASCAR's longest race was a monument to tedium that only resonates with the participants involved. Simon Pagenaud's hard-fought win over Alexander Rossi and Takuma Sato (see more coverage in The Line -WG) was everything a spectacular race should be, with Pagenaud and Rossi swapping the lead five times in the last ten laps. Ragged edge car control at 220+ mph speeds in an all-out duel for the biggest prize in racing? It just doesn't get any better.

Every time I hear the hoary refrain that the Indianapolis 500 has somehow lost its luster, I just have to chuckle to myself. "The Greatest Spectacle in Racing" is exactly that. The build up to Race Day, the solemn pre-race festivities honoring the sacrifices of our men and women in the military, and then the start, which remains the most electrifying moment in all of sport. There is simply nothing like the Indianapolis 500, and there is a reason it remains the most coveted trophy in all of motorsport.

Even though many of us are jaded after a lifetime of observing races across the spectrum of motorsport, Sunday's Indy 500 was a reminder of how glorious this sport can be. Being on the edge of your seat for those last ten laps was something to behold, and something to savor and file away in your memory bank. It was truly special and memorable.

Congratulations to Simon Pagenaud and the entire Team Penske effort. And congratulations to Roger Penske on his eighteenth Indianapolis 500 win, an incredible achievement that will likely never be eclipsed, even though he is far from finished. Roger's indelible motivational statement for his racing operation is "Effort Equals Results." And that was on full display on Sunday. And congratulations to the True Believers at GM

Racing and Chevrolet, as they clearly had the measure of Honda in terms of horsepower (although not in efficiency, apparently).

And I should also mention that I thought NBC Sports did a magnificent job with their coverage too. They perfectly captured the spirit of Indy, while delivering outstanding coverage of the racing itself.

And that's the High-Octane Truth for this week.

(Photo by Chris Owens/INDYCAR)

Simon Pagenaud, winner of the 2019 Indianapolis 500.

(Photo by Doug Matthews/INDYCAR)

Roger Penske and Simon Pagenaud at the Monday morning winner's photo shoot at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway.

(Photo by Stephen King/INDYCAR)

(Photo by Doug Matthews/INDYCAR)

Roger Penske, Simon Pagenaud and Tim Cindric.

Jim Clark, Colin Chapman and Team Lotus the morning after winning the 1965 Indianapolis 500.

THE SHOOTERS.

By Peter M. DeLorenzo

Detroit. I consider the photographers who capture the action at races all over the world to be the unsung heroes of the sport. They're continuing the legacy of some of the legendary artists who came before them, people like Louis Klemantaski, Jesse Alexander, Rainer Schlegelmilch, Bernard Cahier, Pete Biro, Dave Friedman and many, many more. As our longtime readers recall, we lost our friend John Thawley last fall. John provided countless scintillating images to our site over the years and we miss him, and his work. So, as a tribute to John, I thought it might be good to feature some of the work from current photographers for our readers to enjoy, including a stunning MotoGP image from Whit Bazemore, who, we're happy to say, is a new contributor to Autoextremist.com.

(Photo by Chris Owens)

(Photo by Chris Owens)Marcus Ericsson in the No. 7 Schmidt Peterson Motorsports ARROW Honda Turbo V6 at Belle Isle on Sunday.

(Photo by James Black)

Zach Veach in the No. 26 Andretti Autosport GAINBRIDGE Honda Turbo V6 during Sunday's IndyCar Race 2 on the Belle Isle circuit.

(Photo by Joe Skibinski)

Max Chilton in the No. 59 Carlin Racing GALLAGHER Chevrolet Turbo V6 early in Saturday's IndyCar Race 1.

Tony Kanaan in the No. 14 A. J. Foyt Racing ABC SUPPLY Chevrolet Turbo V6 during Saturday's IndyCar Race 1 at Belle Isle.

(Photo by Joe Skibinski)

James Hinchcliffe gets into the No. 5 Schmidt Peterson Motorsports ARROW Honda Turbo V6 during Friday's IndyCar practice on Belle Isle.

(Photo by Whit Bazemore/Special to Autoextremist.com)

Danilo Petrucci (No. 9 Mission Winnow Ducati) overcame a furious last lap battle with Marc Marquez (No. 93 Repsol Honda Team) and Andrea Dovizioso (No. 4 Mission Winnow Ducati) to win the Gran Premio D’Italia at the spectacular Mugello circuit. It was Petrucci's first win in MotoGP™ in his eighth season of GP racing. See more coverage in The Line.

(Photo by Dave Friedman)

(Photo by Dave Friedman)

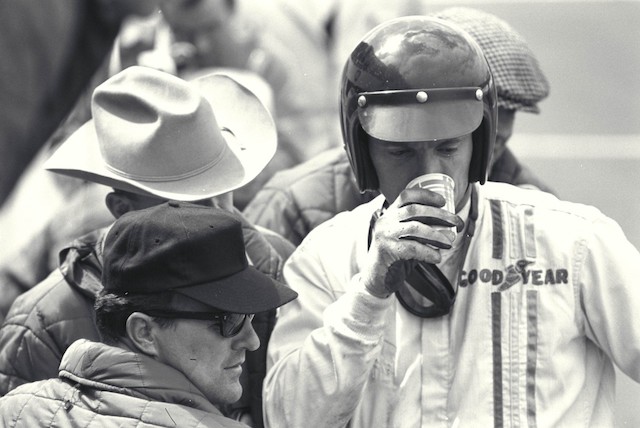

Le Mans, France, June 19, 1966, Denny Hulme, Ken Miles and Carroll Shelby during a pit stop for the No. 1 Shelby American Ford Mk II. Hulme and Miles would have won the race except for a botched attempt by Ford operatives to orchestrate a 1-2-3 finish; instead, they finished second. For Miles, who was probably the most important contributor to Carroll Shelby's - and Ford's - success, it was cruel blow and he remained bitter about it right up to his death in a violent crash while testing the Ford J-car at Riverside in August of 1966. Miles' work on the J-car - which became the Ford Mk IV - was instrumental in the car's development as a racing machine.

MORE BUSH LEAGUE BULLSHIT FROM F1.

by Peter M. DeLorenzo