Editor's Note: We're going to take time this week to have Peter answer some of your motorsport questions. Enjoy (I think). -WG

By Peter M. DeLorenzo

Detroit. Greetings everyone out there in WebVille. As WG said, you have racing-related questions... so I will do my best to answer some of them today. Here we go.

Q: You haven't said much about NASCAR of late except for your cryptic coverage in "The Line." What do you think of the revamped 2021 schedule? -J.T., Orlando, Florida

PMD: I announced earlier this year that we had declared a moratorium on covering NASCAR, although, as you said, we have mentioned (briefly) weekly race results in "The Line." I tried to count the number of revamped NASCAR schedules I have produced over the last decade and I stopped at fifteen. All of those schedules I have suggested revolved around the following: 1. Reducing the number of total races. 2. Reducing (or eliminating) double visits to the same tracks during the season. And 3. Adding more road races. The 2021 NASCAR schedule addresses some of those things, but not all. Dropping the second Michigan race was a no-brainer, because sustaining one race was proving to be difficult enough. Adding road races at Circuit of The Americas, the Indianapolis Motor Speedway and Road America are extremely positive moves. Running on the 3.426-mile road course just outside of Austin will be interesting, to say the least, and getting the Cup cars off of The Speedway's oval is a smart move because the racing was boring and interminable. But the move to add Road America (finally, albeit ten years too late) is huge, and I predict that the stop at America's National Park of Speed - the spectacular 4.048-mile natural terrain circuit in Kettle Moraine country in Elkhart Lake, Wisconsin - will quickly become one of the favorite stops on the calendar for the Cup regulars and the NASCAR brain trust. But - and there's always a "but" with NASCAR - the total number of races - 36 - was not reduced, which is just ridiculous at this juncture. After all the Sturm und Drang that has enveloped NASCAR's declining fortunes over the years, they just couldn't bring themselves to cut the total number of races? Why? And finally, one of the stops at Bristol Motor Speedway is going to be turned into a dirt race, which is a gimmicky idea that should have been left in one of the conference rooms in Daytona Beach, never to see the light of day. It's apropos of nothing and a monumental waste of time, but that has never stopped NASCAR from doing something stupid before, so here we are. And finally, moving off of the schedule, you'll notice that we don't mention Sunday's Talladega "race" in this week's "The Line." That's because it was a Shit Show from start to finish and doesn't deserve to be mentioned. NASCAR clings to the notion that multiple wrecks and the massive destruction of cars is "good television," giving not one single thought about the money involved and the possibility of injuring drivers. It's simply pathetic and inexcusable.

Q. What are your thoughts on the current state of F1? -S.C., Athens, Georgia

PMD: How should I begin? I don't like most of the new "antiseptic" circuits at all. I don't like the look of the cars, and I especially despise the sound - or lack thereof - of the cars. I've written repeatedly that F1 should "bring back the scream" and I haven't moved off of that position one bit. Without that visceral sound appeal - the kind that sends shivers up your spine - F1 is lackluster and far too tame. And I don't like the way the FIA conducts its race "meetings" either. Everything is formulaic and relentlessly predictable. Why bother with three-day meetings or three qualifying sessions? They pretty much know what is going to happen even before they get to the tracks they run on. They could easily compress the schedule into two days and no one would know the difference. I do appreciate the driving talent, however, as I have stated repeatedly.

Q. What do you think of INDYCAR lately? -R.G. Toronto, Ontario, CANADA

PMD: Let the whining from the F1 purists begin, but INDYCAR is the best open-wheel racing series in the world right now. The established stars have prodigious talent - I think Scott Dixon is one of the three best drivers in the world - and the up-and-coming young talent is simply superb. INDYCAR's upward momentum was on full display in Indianapolis over the weekend, and Race 1 of the doubleheader (see "The Line" -WG) was the best - and most ferocious - road racing that we've seen in this country since the glory days of CART. The fact that Chevrolet and Honda will continue to support the INDYCAR series going forward with improved, 900HP Direct-Injected V6 Turbos is fantastic news as well. As good as all of this is, the addition of a third engine manufacturer would be icing on the cake, and I think it will happen.

There were many more emails, but I think that should give you an idea of my thoughts on racing of late. I still love IMSA - especially the GTLM class - and it puts on a far better show than any WEC-sanctioned race you can mention. It's not even close, in fact.

The coming together of those two series - IMSA and WEC - and reaching common ground is a very good thing and crucial for sports car racing going forward. I just hope the French don't screw it up somehow, as is their wont.

And finally, most of the questions we received ask what my favorite form of motorsport is at the moment, and I can say unequivocally that it is MotoGP. The sheer talent and artistry involved in mastering those monster machines is awe-inspiring to see every time they race. It is almost incomprehensible what those riders can do on those machines, and it never, ever gets old.

And that's the High-Octane Truth for this week.

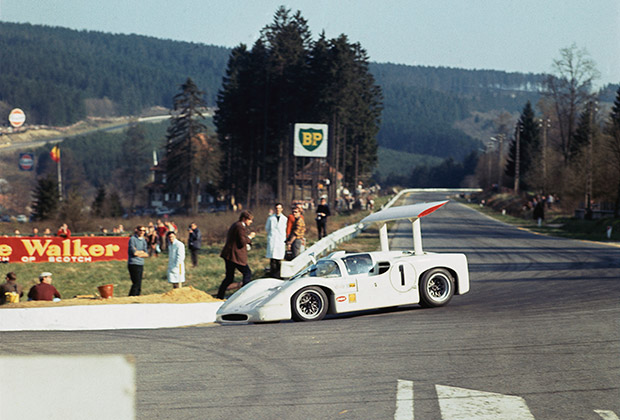

(Photo by AE Special Contributor Whit Bazemore)

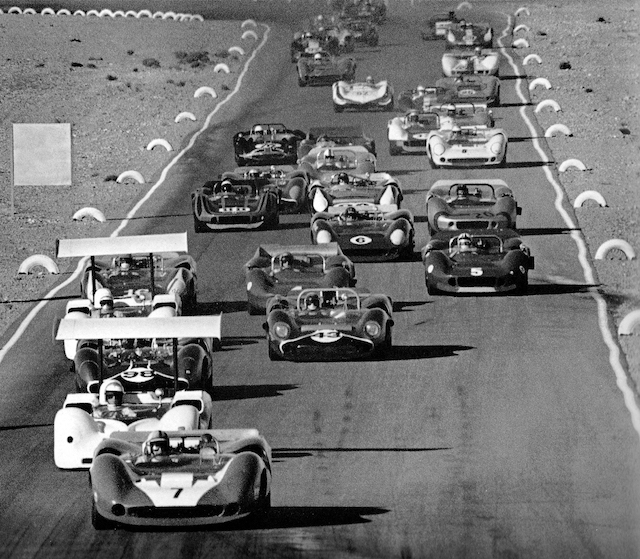

(Photo by AE Special Contributor Whit Bazemore)

Fabio Quartararo (No. 20 Petronas Yamaha SRT) at Circuit of The Americas in 2019.