Editor-in-Chief's Note: Still in the throes of the COVID-19 crisis, racing finds itself on hold, and this terrible situation we all find ourselves in is doing real harm to the sport itself. It's clear that some teams that we've become familiar with in recent years won't survive this forced inactivity. As I've said many times before, iRacing is a fine training ground for drivers - especially as a learning tool for new circuits - but as a substitute for real racing? I'm sorry, there's just no frickin' way. You only have to review the absurdity that went on at the virtual Indianapolis Motor Speedway on Saturday to see that. So as we all endure this Giant Pause, I thought we'd revisit one of my most-requested "Fumes" series - about favorite racing cars. It never gets old. -PMD

By Peter M. DeLorenzo

Detroit. Anyone who has grown up in and around the sport has developed a list of favorite racing cars from the time they were kids. It usually started along the way with favorite model building kits or slot car sets, but we all developed our favorites, which we've all added to over the years. I am no exception. As a matter of fact, my list is extensive and at times convoluted, and by no means is it meant to be some sort of be-all and end-all, but I'm going to throw it out here anyway. (Yes, everyone has their lists, so if you have favorites to add, feel free to do so in Reader Mail - WG)

This is going to be a rambling discourse, so bear with me (and it's Part I because I'm sure I'll forget a bunch of cars, so I'll continue this discussion another day). For starters, I loved the Mercedes-Benz 196R "streamliner" introduced in the 1954 season. To this day it is absolutely stunning in person. And from an earlier era, the Auto Union racing cars were fabulous, especially the mid-engine Type C.

I loved the classic early Porsche racing cars, of course, especially the coupe that ran at Le Mans in 1951 and of course, the little coupes that ran in the Panamericana race in Mexico (which heavily influenced the look of the original Audi TT street car). While I'm on Porsche, I loved the 917 (but surprisingly in the one-off psychedelic Le Mans livery, not the Gulf colors). The early 911 RSRs (particularly in IROC configuration) and the look - and especially the sound - of the current IMSA 911 RSR. I am skipping over countless cool Porsche racing cars, but I have to mention the all-conquering Porsche 917/30 raced in the 1973 Can-Am season by Mark Donohue, and my all-time favorite racing Porsche (designed by Ferdinand Piech, no less), the fabulous little 908/3 designed specifically for sprint events like the Targa Florio and the Nurburgring.

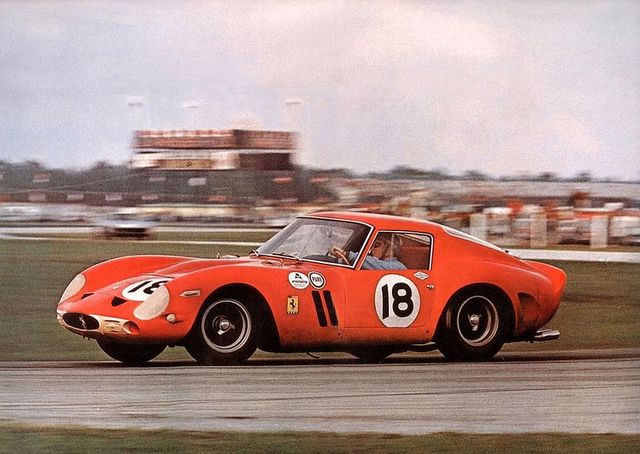

How can you not have a list without Ferrari? I loved the sports racing cars from the 50s, the Testa Rossa just being one of a long list of favorites. I loved the 156 "shark nose" F1 car, so elegant but provocative in its simplicity. And the GTO. But my all-time favorite racing Ferrari? The magnificent 330 P4 (the Penske Sunoco Ferrari 512M was spectacular, too, but the P4 does it for me).

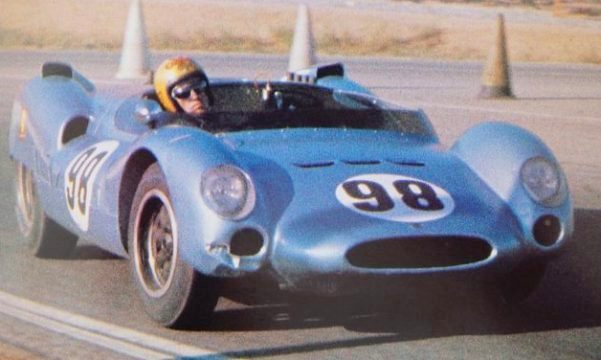

And then the Ford-powered racing machines. As readers know, the Shelby American Cobra is one of my all-time favorites, and I especially loved the early competition cars in all the myriad configurations, especially Ken Miles' favorite No. 98. And the perpetual favorite, the beautiful Peter Brock-designed Cobra Daytona Coupe. Then there are the short-lived but still great Ford-powered Cooper Monaco "King Cobra" sports racers from the early 60s, or the Shelby GT350 Mustangs (the car I learned to drive a stick with). And of course all of the Ford GTs and their variants, especially the 1967 Le Mans-winning Mark IV driven by Dan Gurney and A. J. Foyt (but I do love the original, unadorned Ford GT40 Mk 1 for its purity). Then there were the fabulous NASCAR Fords prepared by the Wood Brothers for Dan Gurney. And even the drag racing Ford Fairlane Thunderbolts, which were bad-assery to the first degree. And of course the Bud Moore Engineering Boss 302 Mustang Trans-Am cars.

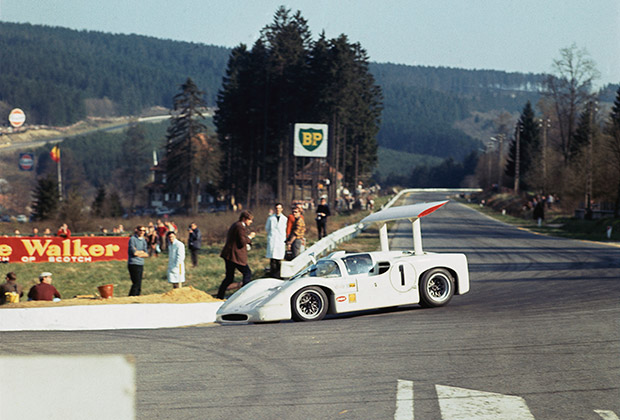

If anyone has followed me on twitter (@PeterMDeLorenzo) of late, I have been doing a historical tour of great racing cars and tracks in photographs, and it's no secret I reserve a special place in my heart for Jim Hall's fabulous Chaparral racing machines. I love all of them in all of the variations, but the 2E that Hall and Phil Hill dominated the Laguna Seca Can-Am weekend with in 1966 is right up there. I also loved the 2D and 2F coupes designed for endurance racing.

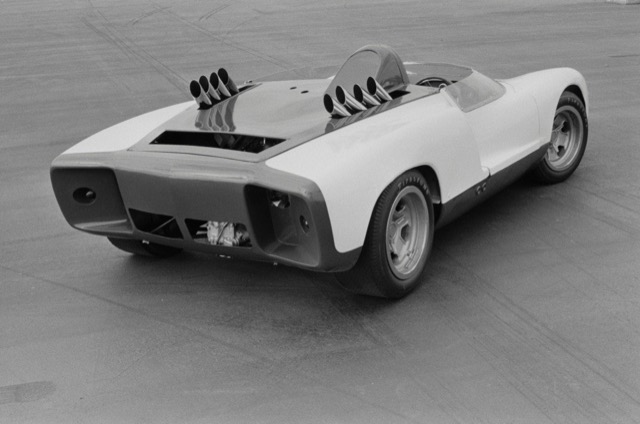

And I can't forget to mention the fabulous front-engine Scarab sports racers, built by Troutman and Barnes and powered by Chevrolet. Or the Bill Thomas Cheetah, which came to be just as the mid-engine revolution hit. Or the 1968 Penske Racing Trans-Am Camaro. (Yes, I know, the list goes on and on.)

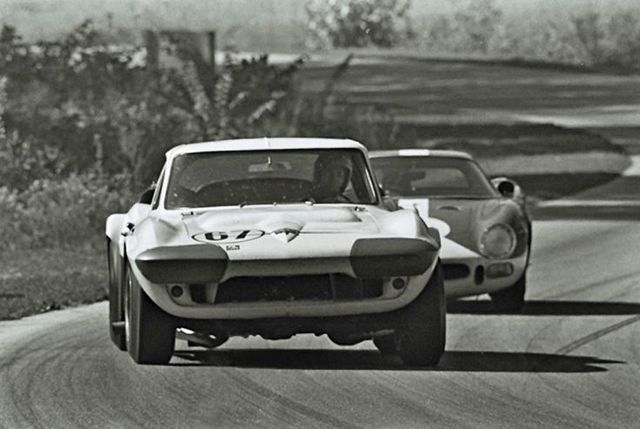

The Corvette is always front and center when it comes to my favorite race cars. I loved the factory-developed 1957 Corvette SS, which appeared at Sebring, and the 1960 Briggs Cunningham Le Mans cars. And of course the fabulous Grand Sports - especially in John Mecom Racing Team Nassau livery - which have a visceral appeal that never gets old.

And, full disclosure, I loved the Owens/Corning Fiberglas Corvette Racing Team machines raced by my brother, Tony. The remarkable liveries of those machines, created by legendary GM design ace, Randy Wittine, were heavily copied and still resonate to this day. (I also preferred Randy's design for the Bud Moore Mustangs we purchased and campaigned in the 1971 Trans-Am season over the factory Butterscotch Yellow cars, and our OCF Trans-Am Camaros were beautiful too.) My favorite Corvette that my brother raced was the black 1968 "A" Production roadster that he won the June Sprints at Road America with (see below). This was right before the Owens/Corning sponsorship deal came together. And the current C7.R racers are fantastic, although not my favorite liveries by any stretch.

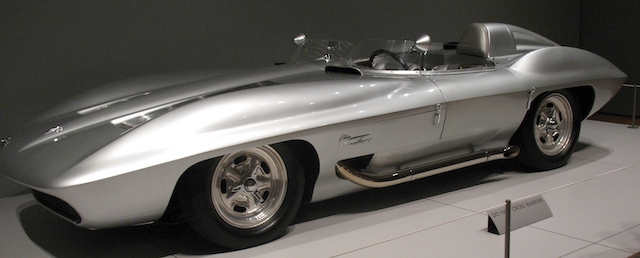

But my all-time favorite racing car is the original 1959 Corvette Sting Ray racer. GM Design icon Bill Mitchell purchased the leftover "mule" chassis from the Corvette SS program and enlisted some of the most talented designers at GM at the time - including a 19-year-old Peter Brock, who did the original sketch - to come up with the design language for the car. The result? Simply one of the most magnificent looking machines of all time. You really need to see the car in person to truly appreciate it.

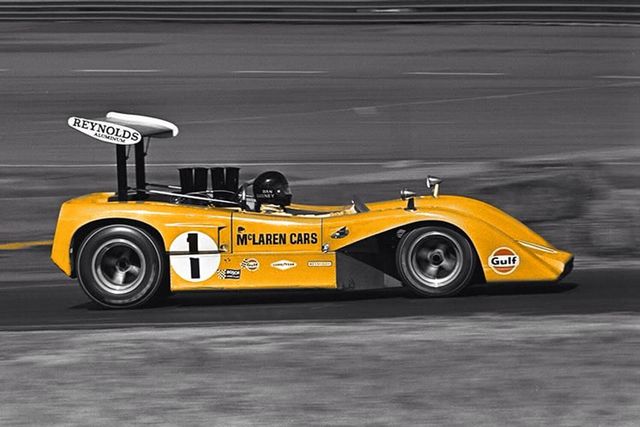

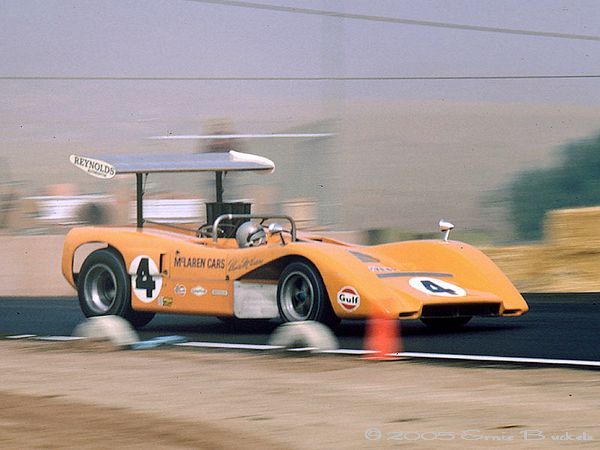

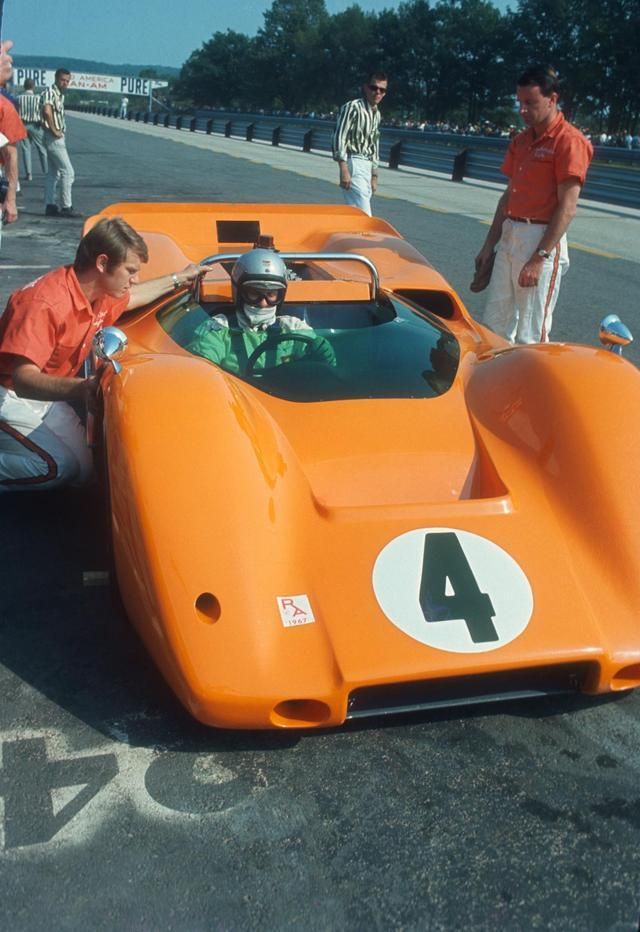

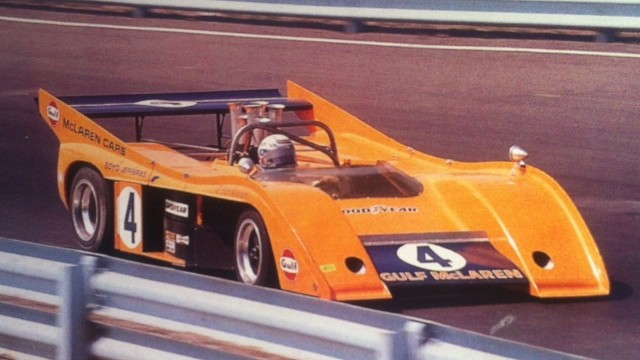

I look forward to continuing this discussion. I haven't even covered the F1 cars, the Indy cars, the sports prototypes (Lola T70 Coupe, anyone?) and my other all-time favorite racing machines: the Team McLaren Can-Am cars.

And that's the High-Octane Truth for this week. The Mercedes-Benz 196R "streamliner."

The Mercedes-Benz 196R "streamliner."

The Auto Union Type D.

The Auto Union Type D. Dan Gurney in a Ferrari Testa Rossa, at Goodwood, 1959.

Dan Gurney in a Ferrari Testa Rossa, at Goodwood, 1959. The Troutman and Barnes Chevrolet-powered Scarab sports racer.

The Troutman and Barnes Chevrolet-powered Scarab sports racer. The Ferrari 250 GTO.

The Ferrari 250 GTO. Phil Hill in the Ferrari 156.

Phil Hill in the Ferrari 156. (Dave Friedman photo)

(Dave Friedman photo)

Dave MacDonald in the Cooper Monaco King Cobra Ford. (Dave Friedman photo)

(Dave Friedman photo)

Dan Gurney in the factory Shelby American Cobra roadster, Riverside, 1963.

(Dave Friedman photo)

(Dave Friedman photo)

The Shelby American Cobra Daytona Coupes at Le Mans, 1964. Phil Hill in the Chaparral 2E, Bridgehampton, New York, 1966.

Phil Hill in the Chaparral 2E, Bridgehampton, New York, 1966.

The 1959 Chevrolet Corvette Sting Ray racer.

Elkhart Lake, Wisconsin, June 15, 1968. Speaking of favorite racing cars, of all the cars my brother Tony raced the No. 50 Hanley Dawson Chevrolet '68 Corvette 427 L88, which was painted Black with a Blue Stripe, has to be one of my favorites. Here he is on the way to the win in "A" Production in the June Sprints at Road America.